The Best Books of 2024

My favorite books I read this year

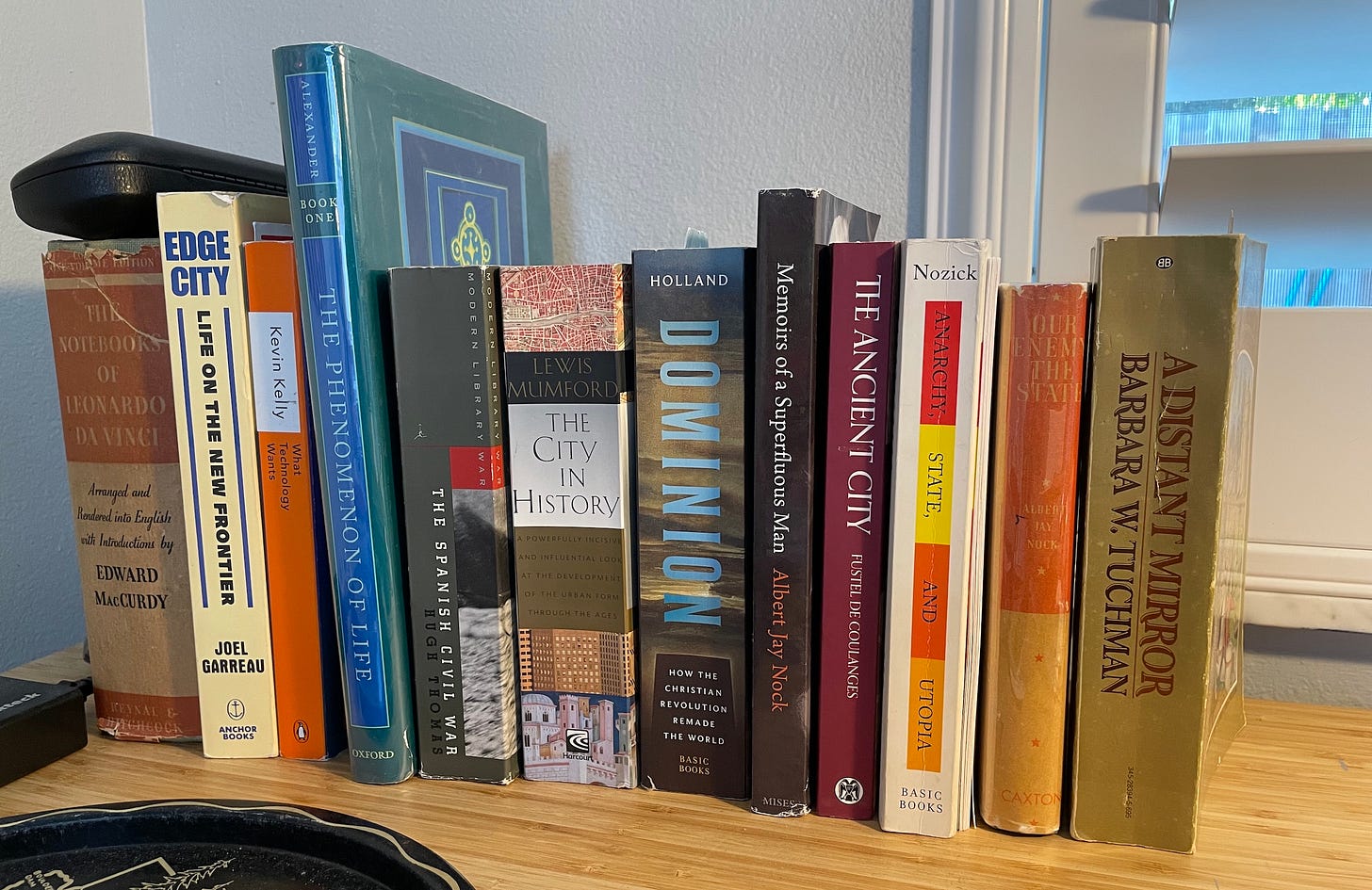

Though it felt like I was less productive reading in 2024, when I look back at the list I was able to visit some excellent stuff that’s been on my list for years.

I finished 24 books total this year. In the past I let the zeitgeist of recommendations influence a lot of my selection: current books being talked about by their authors on podcasts, things making the rounds in annual rankings. Nothing wrong with this approach, you at least get plenty of points of reference to check out as companions for reading.

But this year I wanted to go back and read more time-tested classics. The list isn't all "great books" canon, but I dipped into the older, more lindy stuff more than I used to.

Here's a selection of my favorites, in a rough order of most important or impactful first. But not a hard "ranking" or anything.

The Beginning of Infinity

David Deutsch, 2011.

Dare I say this is the most important work of popular science and philosophy of the last 50 years? 75 years? It's the best work around at understanding Karl Popper's philosophy. For anyone interested in Popper's ideas on error correction, falsifiability, and fallibilism, I'd direct them to Deustch over Popper's work.

In a blend of philosophy, science, and history, Deutsch argues that the growth of knowledge is not only unbounded but also central to solving problems and advancing civilization. His compelling thesis—that progress stems from the interplay of error correction and the creation of new explanations—challenges the notion of limits in science, technology, and morality. It's inspiring and demanding, requiring you to grapple with concepts like the multiverse, the meaning of creativity, and the fallibility of human understanding.

This is the sort of book that sticks with you. If you aren't already one, you'll come away an optimist.

How Buildings Learn

Stewart Brand, 1994.

Every now and then you find a book that transcends what’s advertised. By its cover, How Buildings Learn is about buildings and architecture — and it is a phenomenal review of the process of architectural design — but there's so much more.

I wrote an extensive review with my notes going into more of what makes HBL so profound. Though the label says architecture, the concepts transfer well outside the stated subject to areas like team building, software, governance, and culture. It's really an analysis of how complex systems adapt and change, with architecture as its sample specimen. See also my post on Brand’s concept of pace layering, a concept born in this book.

Orthodoxy & Heretics

G.K. Chesterton, 1908 & 1905.

Until this year the only Chesterton I'd read, outside of quotes and references, was The Man Who Was Thursday, which is fiction. But what he's most famous for are his works of philosophy, literary criticism, and the subject of these two pieces: Christian apologetics.

I've never been a practicer of religion, and though Chesterton — a committed orthodox Christian and later Catholic — explicitly defends the faith in these books, I found them much more insightful as analyses of morality. And the man had a way with words. Though his style is florid at times, he's eminently readable. I actually read Orthodoxy twice in a row, something I really should do more often.

The Iliad

Homer, 800 BC.

It's the foundation of storytelling and the Western canon, yet somehow I'd never read it cover to cover. Going back into the classics is so enjoyable for how much you find the influences in things we consume today.

War, fate, free will, mortality, loyalty, wrath and its consequences. There are rich lessons here, and the timelessness of its themes (pushing 3000 years old) speaks to the fundamental, unchanging nature of the human condition.

Hyperion

Dan Simmons, 1989.

Thought I've read plenty of science fiction, including other space operas, I've never read anything like Simmons's Hyperion Cantos. Structured in the style of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales with multiple POV characters, it's packed with literary flourish (shares its name with a John Keats poem, and Keats is very important to the story), both in its references and style. But the narrative, the world-building, the politics, the emotion. Hyperion had its acclaim when it came out in '89, but I still think Simmons is underrated as a writer.

What Technology Wants

Kevin Kelly, 2011.

Kelly makes the case here that technology is an extension of life, a new lifeform — a "new kingdom" alongside plants, animals, fungi, etc. He calls this the "Technium", and spends the bulk of the book explaining the myriad ways technology has evolved to such an advanced state that it's beginning to exhibit its own evolutionary, adaptive mechanics like natural selection and survival of the fittest. While I'm aligned in many ways with Kelly's argument, I wrote about my problems with the lack of human agency you must believe in to buy into the Technium as a self-motivated entity whole-cloth.

Brian Arthur's The Nature of Technology covers similar ground, but from a more root-and-branch understanding of the process itself versus the more philosophical and sociocultural angle Kelly takes in WTW.

Valuable Humans in Transit

qntm, 2022.

A collection of short stories from qntm, the online pseudonym of writer Sam Hughes. It's basically impossible to put into words the genre and creative vision of his fiction. He'll take the strangest of concepts and explore them in formats and setups you've never read before. It's hard to know what else to say except if you like speculative fiction, just read it.

The Abolition of Man

C.S. Lewis, 1943.

Like Chesterton, Lewis is also well known for his defenses of Christianity, like The Screwtape Letters or Mere Christianity. But this one is not specifically about Christianity, but rather a collection of essays that vigorously critiques moral relativism from all angles.

Lewis proposes what he calls the "Tao": a universal set of principles and morals that transcends time and culture. As he argues, when objective values are undermined and replaced by subjective preferences or purely utilitarian thinking, individuals lose their capacity to recognize true virtue and become susceptible to manipulation by those in power.

The War of Art

Steven Pressfield, 2002.

This book came to me at the perfect time. It showed up in the mail with no clear sender, but clearly someone who knew my taste and preferences. I had heard of Pressfield and seen him on podcasts talking about his ideas on creativity, and The War of Art is probably the best distillation of his ideas on the subject.

Pressfield's main idea is what he calls "Resistance": his term for the force that hinders individuals from pursuing creative goals. Procrastination, indecision, self-sabotage, and imposter syndrome all flow from the same fount of Resistance. In a high-density format, he gives insightful advice on how to fight Resistance primarily through discipline, and treating your work like a professional. Get up, practice, practice, practice. Commit and take it seriously. Put the reps in. Stop trying to get worried about the end result before you start — just keep swinging. A fantastic read for pretty much anyone interested in creativity or building things.

I later found out that my sister-in-law sent it to me. The perfect gift!

Beauty

Roger Scruton, 2011.

I've been on a kick lately diving into the subject of what defines "good taste". It's always felt like one of those "you know it when you see it" things — taste is when you know how to have good taste. A circular reasoning with no starting point. There'll be a future piece on the newsletter about this topic once I spend more time on it. Clearly there's some hard-to-define set of properties that constitute tastefulness.

Scruton's Beauty was part of my journey on this. What we mean when we say something is "beautiful" similarly escapes a simple definition. Scruton argues that beauty is not just subjective preference — "the eye of the beholder" and all — but an objective quality that contributes to our moral and emotional well-being. He says beauty enriches our experiences, fosters a sense of harmony, and is fundamental to art, nature, and everyday environments. That sense of harmony, or some sort of richer alignment and fitness to the surroundings, in my read, is a big deal in differentiating the sort of beauty he's talking about — something deeper and richer than superficial looks.

The Pathless Path

Paul Millerd, 2022.

Since I've recently left my company after launching and growing a SaaS product for the past 14 years, the time's been ripe to consider deeply what kinds of things I might do next. Plenty of ideas have bounced around: things to start, products to incubate, people to work with. After so long devoted to the same project, the array of options to pursue is huge.

Paul Millerd makes a strong case for the benefits of the pathless path: the alternative approach to work and independence that trades the consistency and stability of the regular 9-5 for freedom, optionality, and fitting work more comfortably with the way you want to live. Same with the War of Art, now was the perfect time for me to read this.

Letters to a Young Poet

Rainer Maria Rilke, 1929.

Between 1902 and '08, Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke corresponded with another poet, Franz Kappus, who was seeking advice. And Rilke bangs out some incredible pieces of profound depth on creativity, introspection, and how to develop trust your own creative instincts. Hat tip to my friend Thomas Steele-Maley for pushing me to check this one out. Phenomenal stuff.

The Origins of Totalitarianism

Hannah Arendt, 1951.

Observing first hand the horrors of totalitarianism of both the Soviet and German varieties in the early half of the 20th century gives Arendt's work on the subject an unmatched level of reality and presence. If you're interested in the historical lineage of political philosophies — a "how did we get here?" for understanding this special strain of dictatorship — this is one of the original classics to give you the background.

Foundry

Eliot Peper, 2023.

Eliot Peper is one of my favorite fiction writers working today. His genre (if you can put him in one) is a hybrid of sci-fi, technology, and speculative fiction that brings fresh ideas to each novel. This one's a fast-paced spy thriller that I blitzed through in a couple days. Loved it.

Make to Know

Lorne Buchman, 2021.

The main premise of this book is that the act of creating is inextricably linked to the goals we pursue in creative endeavor. In other words, there's fundamentally no way we can clearly define the end state without getting started and working on our work.

There's a lot of resonance in Make to Know with Pressfield's ideas in War of Art. It's something I believe in deeply, that we must start building to know what we're building. That planning and deliberating and wondering leads to diminishing returns, and ultimately we have no idea how to work through the details without being "in it".

How to Listen to Jazz

Ted Gioia, 2016.

I've been a jazz listener for a couple decades now, yet my knowledge of the genre still feels superficial. I mean the mechanics of the art form, how to differentiate styles, the geographic lineages of the music and the culture around it. Ted Gioia is an avid proponent of building expertise through active participation: through listening, rather than having to be an academic or some sort of professional. I wrote up my thoughts on this one a few months ago. A great primer for either people brand new to the genre, or even journeyman listeners like me.

Great recs--have you read Benjamin Labatut?

thanks for the shoutout - lots of great books here