Pace Layers

The hidden architecture of resilient systems

A forest is a complex ecosystem made up of thousands of organisms living, evolving, interacting with each other, and changing over time.

At the top of the hierarchy are the leaves, changing annually, growing, dying, and shedding in a year-long seasonal cycle. Next there are branches, fewer in number and slower in growth. Then the whole tree itself, changing over decades. The tree sits in a stand of dozens, and the stand in a forest of thousands of individual trees. The forest within a biome, the biome in a region with a particular climate.

You get the idea.

All natural ecosystems evolve in layers like this that connect to each other, but move at different speeds. You can imagine other systems with similar structures: your body is made up of proteins, DNA strands, organelles, cells, membranes, organs, a skeleton, and eventually, your whole body. Cells are being generated but also dying off at almost the same rate. Slower layers like the nervous system take a long time to heal (if ever) when subjected to injury.

Seeing complex systems this way — as layered collections of variable-speed elements — is a useful framework for understanding why we have a hard time changing them.

Stewart Brand noticed this recurring pattern in the anatomy of systems, which he called pace layering.

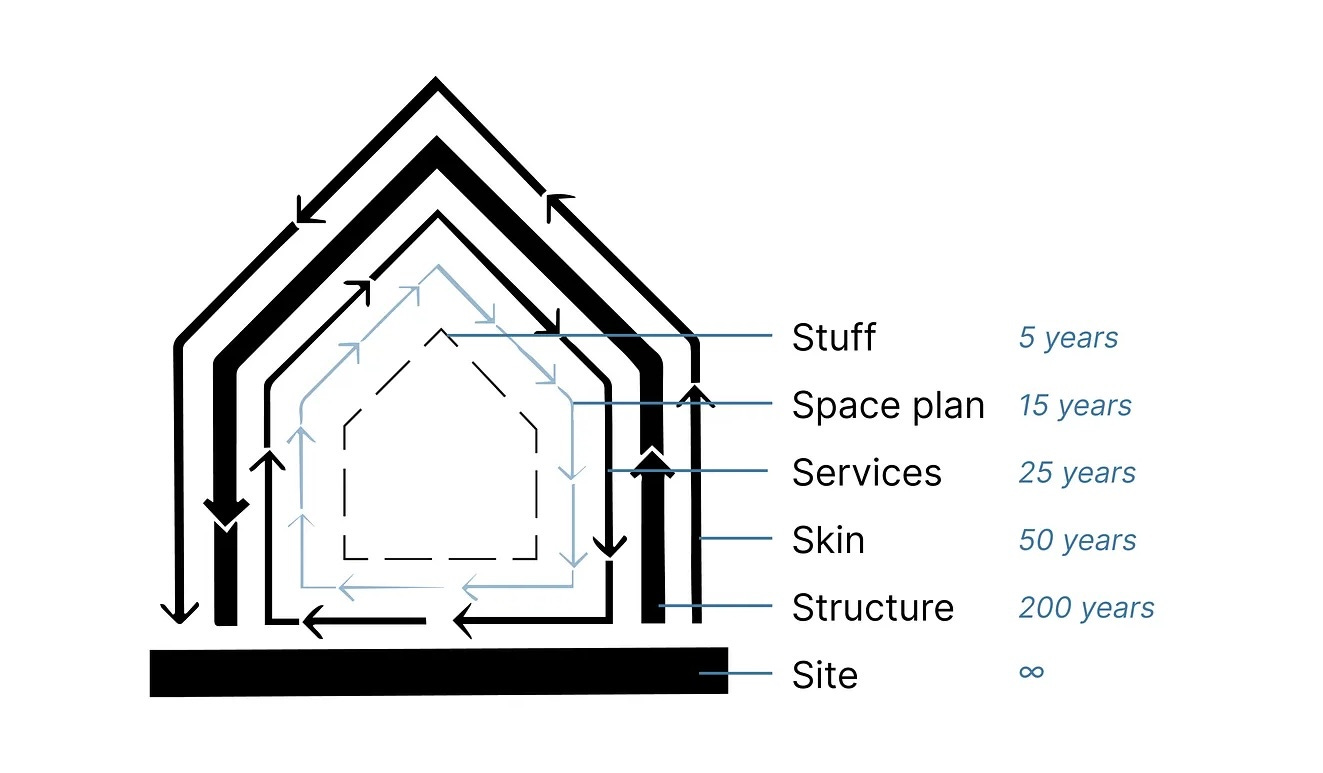

The concept builds on an observation made by architect Frank Duffy, who noticed a hierarchy in the components of buildings. In his book How Buildings Learn, Brand expanded this observation into a model he termed “shearing layers,” which describes how different parts of a structure change at varying speeds. Site → Structure → Skin → Services → Space plan → Stuff. Each must survive or adapt on different timelines. When architecture fails to account for the different rates at which users need to modify these layers, it results in rigid, non-functional design. Buildings where Services or the Space Plan are overly inflexible are difficult to adapt to users' changing needs.

In his later book The Clock of the Long Now, Brand expanded the concept of shearing layers to a civilizational scale:

At the bottom, nature moves along on its own eons-level time scale. In the middle, governance and culture shift with generations. Infrastructure and commerce in the range of years. And on the surface, fashionable trends flare up and die out with sometimes daily regularity, like the turbulent wave tops in a stormy ocean. Each layer serves a function:

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

(Stewart Brand, The Clock of the Long Now, p. 34)

Variance and novelty churn around at the top. Constraint, guidance, and direction provide stability from the bottom.

Seeing the world through this lens — not only of scale, but also of time — has distant reach to so many other domains. It's a fundamental characteristic of how systems work and adapt to change.

The fast flurry of activity at the top of a pace layered system creates a testbed for new ideas. In the forest, each individual tree can try out different evolutionary adaptations. New survival strategies are tested in numbers not possible if entire ecosystems had to move together. If one tree tests a new trait that turns out not to work, only a single organism is at risk, not the whole forest.

Because upper layers move faster they can also rebound faster. A forest fire or a passing herd of elk causes some damage, but only at the surface level upper crust of our strata. The bark and branches and leaves may get eaten or burn off, but in a few weeks they bounce back.

Pace layering builds resiliency into complex systems. The fast layers shield the slower ones from shocks, while selectively transmitting changes down through the layers, allowing slower ones to incorporate those adaptations. But some changes propagate too fast.

Some of the worst cases of system shock happen when change shakes to lower levels too rapidly. Look at the collapse of the Soviet Union. A rapid change in the governance layer caused wreaked havoc in the layers above: massive instability on a national scale, rippling through the whole system for decades. In this case, a totalitarian government imposed rigidity on commerce, infrastructure, and even fashion, and didn't allow for the necessary shifting and experimentation required for the system to maintain resilience.

Drawing sharp lines between layers actually draws an inaccurate picture of how a thriving system works. A more accurate diagram would show smoother gradients across the transitions between layers.

Resilience comes from allowing this gradient — this slippage — at the junctions between layers. Each layer, above and below, must allow for give and take from its neighbors. Slow layers must permit some influence at the edges, and fast layers must slow down to maintain a workable interface with the slower. The layers need to be able to negotiate with one another. If the fast ignores the constraints of the slow, you get discontinuous instability. If the slow never bends to the fast, you get stifling stagnation. We see this regularly in public policy: overregulation stifles innovation, but a complete lack of governance structures leads to crises and potentially very destructive creative destruction. Moving too quickly without considering the purposes of the slower systems leads to dismantling well-established ideas — like Chesterton's fences — in the reckless pursuit of the new. The stability of the upper layers depends on the steady, reliable predictability of the slower foundation underneath.

Slippage allows systems to evolve gradually — through trial and error — and incorporate the things that work, while shedding or resisting the things that don't.

The slippage zones where layers come together are also where we get conflict and disagreement. Sometimes a fast moving R&D team in a company wants to plow forward with a new idea, but the conservative finance team wants to proceed more cautiously with company resources.

Yet these transition zones are where all the most interesting things happen. They're home to the system's "biodiversity": fertile ground for innovation, evolution, creativity, disruption.

Paul Saffo describes the action in the transition layer as "constructive turbulence". As a fast layer rubs up against a slow one, eddies of interesting new things spin off in unexpected and interesting directions.

As a Floridian, the concept of a turbulent mixing zone brings to mind an estuary. A fresh water creek flows along the coast and meets the salty ocean. Two contrasting ecosystems support different species of plants, fish, birds, and insects. Where the two meet we get intertidal movement — a piece of land sometimes inundated and sometimes dry. We get grassy areas, marshes, rock beds, beaches. A wide variety of different organisms collide like a clash of separate cultures. Forcing these differing layers together creates a vibrant hotbed of activity you don't find on a flat, uniform seabed.

You can also encounter major discontinuities when change propagates over many layers too suddenly for others to adjust.

The tectonic plates of Earth's crust move at a few centimeters a year. But once in a while, a sudden burst of activity (an earthquake) shakes the foundation in seconds. Suddenly the nature layer catastrophically disrupts commerce and infrastructure.

On the flip side, a sudden innovation like the Internet, emerging up in the commerce and infrastructure layers, rapidly reshapes the world. Change cascades downward, affecting the culture in years rather than decades. Disruptive technologies have this effect of crossing pace layers much quicker than normal.

Another important angle, beyond speed and scale, helps explain why the layers behave the way they do: each layer has a different relationship to risk.

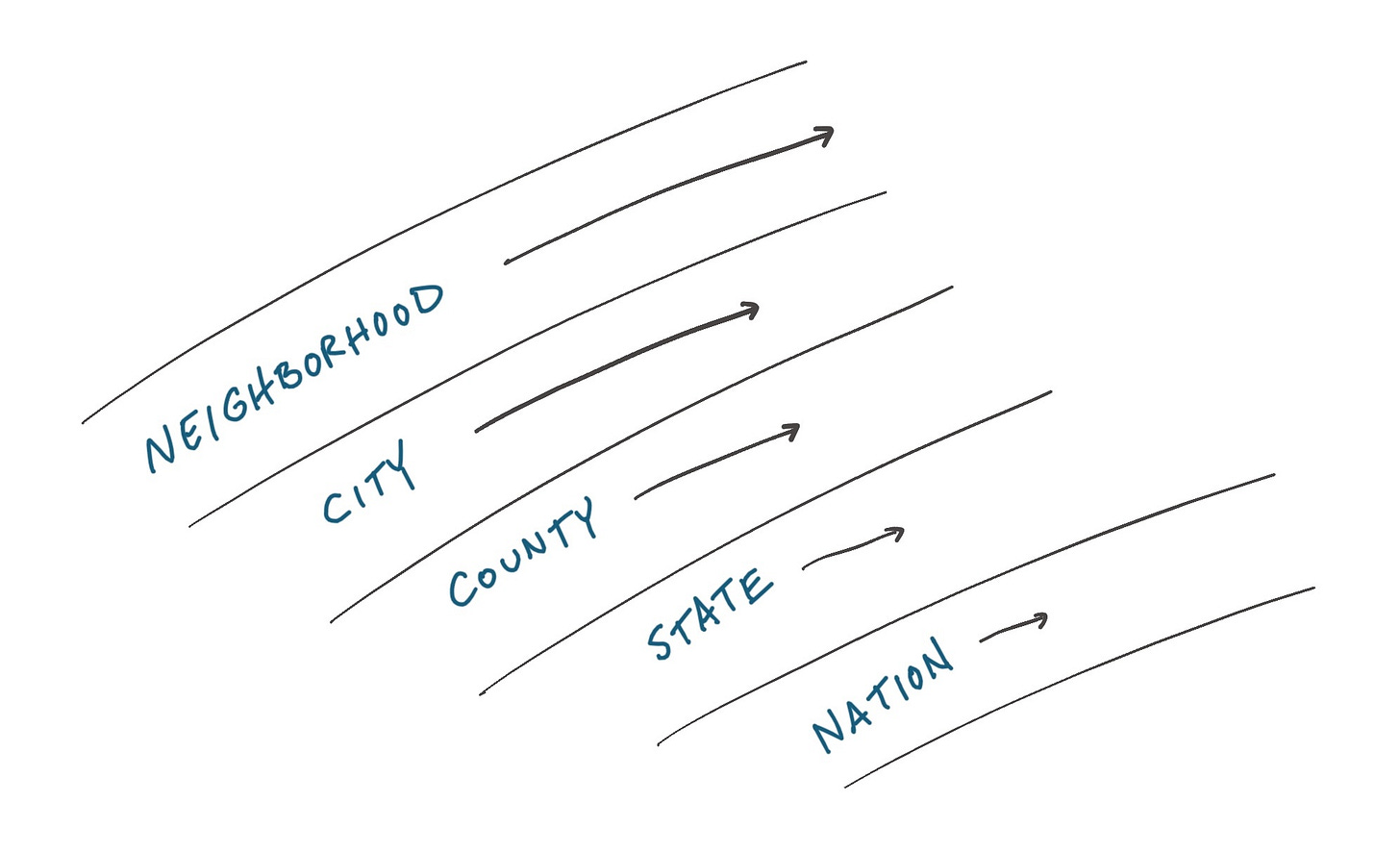

A great example of this pace ↔ risk relationship shows up in the federalist model of government. In the United States, the federalist system is a hierarchy:

Governance begins with a broad, foundational definition of policy: the fundamentals of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. As you move up through the layers, powers become more and more specific, with policies more explicitly defined. And at the top you might find a neighborhood association even specifying what color you can paint your house. This hierarchical model of rules and regulations allows for wide experimentation, all built on a strong foundation of secured natural rights.

Neighborhoods and cities can try all sorts of ideas that are unworkable when imposed nationwide. But looking at it through a risk/reward lens, it makes sense. An unworkable failed policy tried in an HOA only creates downside for a few hundred families. A failed policy imposed by Congress on the nation as a whole: bad news. As policies get tried and tested in smaller jurisdictions, the good ideas can be assimilated and adopted by larger domains.

In the slower-moving layers of state and federal government, the downside risk of failure is too high for fast-moving experiments to be conducted across the country. But in our families, neighborhoods, and cities, we can afford to move fast and break things. It reminds me of this quip from Nassim Taleb's Skin in the Game that touches on this scale variance:

A saying by the brothers Geoff and Vince Graham summarizes the ludicrousness of scale-free political universalism.

I am, at the Fed level, libertarian;

at the state level, Republican;

at the local level, Democrat;

and at the family and friends level, a socialist.If that saying doesn’t convince you of the fatuousness of left vs. right labels, nothing will.

You see this same gradient of risk tolerance in companies. The fast, risk-taking startup versus the slower, conservative Fortune 100 firm. Slower-moving layers are less able to recover from shocks than fast ones, so they must proceed with more caution. In the startup, there's far less to lose.

With age, my mind seems to sink to lower levels in the hierarchy. "Current things" are more likely to hit me and bounce off. We come around to new ideas more slowly. Above us are the teenagers, trying new technologies, listening to new music, pushing new memes, on a weekly or daily basis. We parents underneath can't keep up.

But "keeping up" isn't our role! Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast tries things, slow preserves what works. Resilient, sustainable systems balance this learning and remembering.

Not every meme or new song or fashion trend has staying power, but some do. The ones with notable resonance absorb and influence the culture below. Youth play the role of experimenters, continuously throwing new ideas at the wall — some good, many terrible. The elders carry the torch of tradition, and provide the stable platform of time-tested solutions on top of which the innovators can explore.

Pace layering is one of those ideas with such broad reach that once you learn about it, you see it everywhere.

Thanks for reading. Please like, share, and leave your feedback in the comments if you liked this post.

Great article, adding this to my list of books to read. This reminded me of Paul Cilliers concept of an appropriate slowness. Systems that match the speed of their environment are incapable of learning and committing what matters into their memory