The Best Books of 2025

My favorite books I read this past year

As I was looking over the books I read this year, I went back to look at last year’s list, and was surprised to see I read exactly the same number: 24 books. Nothing particularly significant there, just a funny coincidence.

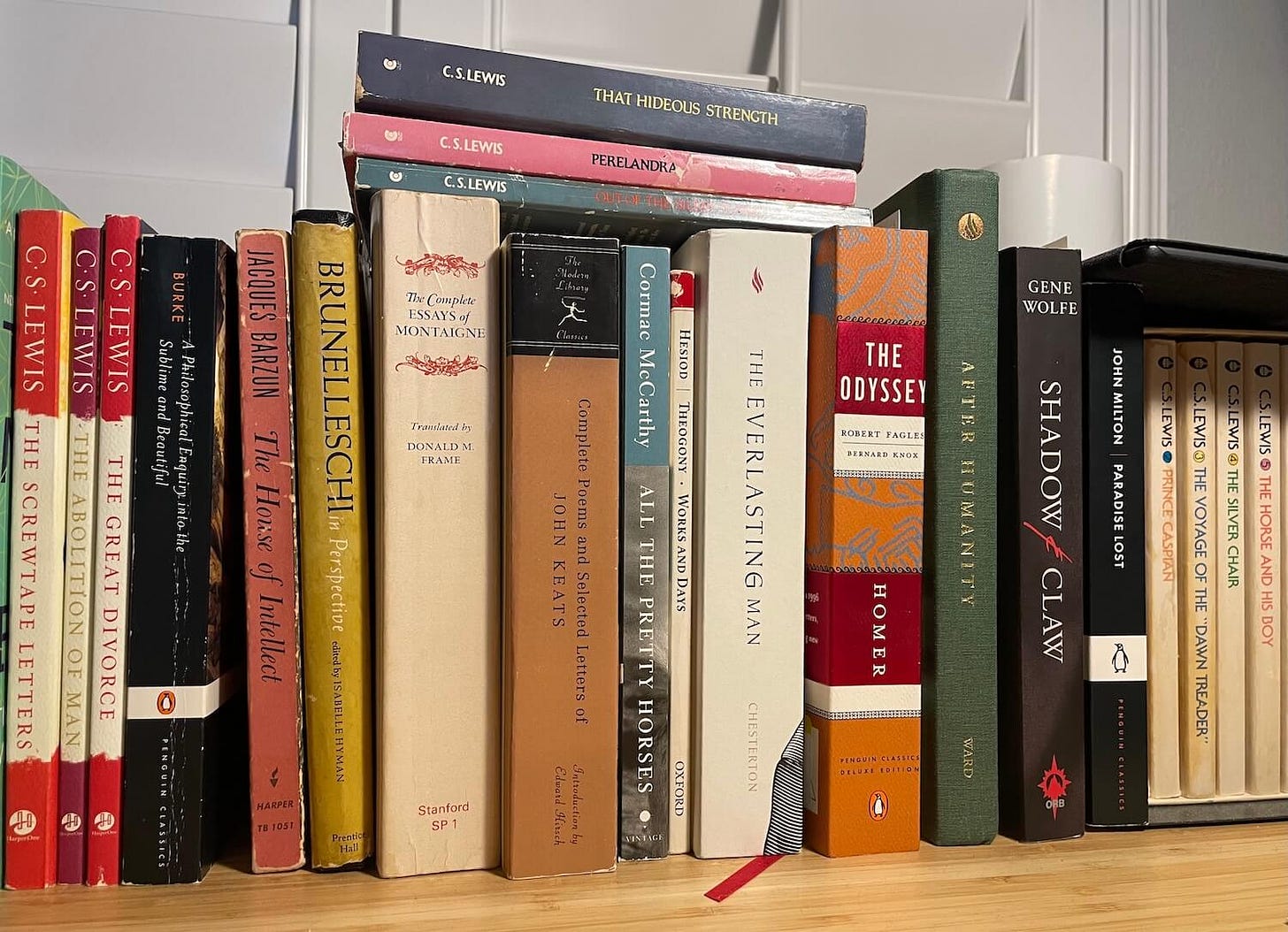

I stopped setting quantity goals a few years ago. And even last year I’d largely quit reading anything current. There’s no top-down set of rules I follow about what to read or avoid, but I’ve made a conscious effort to pick up things I’ve collected and had on my shelves for years.

Book people will be sympathetic to this: we could have an antilibrary with 1,000 books we’re yet to visit, and still go out and buy something new as our next read. It’s impossible to avoid. One great example from this year is Crime and Punishment. I’ve had this copy for I-don’t-know-how-many years. 15? 18? It’s laid there on my shelf, eagerly waiting for the day I’d crack it open. I finally did.

Here’s a selection of some of my favorites from the year, with a few notes about each one.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; Prince Caspian; The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

C.S. Lewis, 1950, 1951, 1952.

The Narnia books are written for children, but like all the best children’s works, they translate so differently when you read them in different eras of your life.

As a kid, these stories come across as simple fairly tales. Fauns, lions, talking beavers, dragons, sea people. You read them more from the perspective of the Pevensie kids in sort of first-person, imagining yourself exploring the frozen Land of Always Winter or the castle at Cair Paravel.

Yet as an adult, and a parent, I get something completely different. I read these more as an observer watching my kids explore the world, discover the moral, find themselves. Plus there’s plenty of richness we can takeaway ourselves as adults. In Dawn Treader, when the Pevensies’ self-centered, joyless, materialistic cousin Eustace goes through a humbling experience after being transformed into a monster, his realization of his own ugliness and arrogance reads much differently as an adult than your literal reading as a kid.

I’m looking forward to finishing the Narnia re-read this year. Relatedly, I’ve listened to a couple of interviews with Michael Ward on his book Planet Narnia, which interprets each entry through one of the medieval “seven heavens” – Jupiter, Mars, Sol, Luna, Mercury, Venus, and Saturn. I had his thesis in mind when reading the first three books, but interested to dig into his analysis after I finish the series.

Turning Pro

Steven Pressfield, 2012.

This is one of those books (along with his earlier The War of Art) that’s lived in my head since reading it. No one gives you a mental kick to get yourself in gear like Pressfield.

The War of Art was all about “Resistance,” his term for the force we must overcome to get any creative work accomplished. It’s inertia, a train sitting still on the track held fixed by gravity, and it’s our job to muster the activation energy to get the train moving.

Turning Pro is about how to professionalize fighting Resistance. To be a pro means to take the work seriously, to prioritize it over other things, to be a grown up, quit making excuses and get to work. The pro doesn’t need the perfect environment to get their work in. They show up and get the practice done whether it’s at the home office, a hotel room, or sitting in the parking lot at the mall.

There are plenty of forces at work that raise Resistance and create an environment that steals our attention. But part of acting the pro is realizing you’re the one with the agency over your attention. You can decide not to hand it over to the distractions, and spend it how you want.

Mere Christianity

C.S. Lewis, 1952.

I’ve been a “nominal” Christian my entire life, yet not a practicing one — certainly not a studied one. Mere Christianity is a great entrance point to the fundamental tenets of Christianity without getting lost in doctrine or denominational differences. Lewis presents his arguments through moral philosophy and clear reasoning, building a case for Christianity that’s accessible. He doesn’t spend time differentiating in the details between Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Presbyterianism, but focuses instead on the core beliefs that unite Christians.

Rather than relying on technical theology or biblical scholarship, Lewis presents abstract ideas in a concrete, practical way, emphasizing how belief fits with human experience: our moral intuitions, our sense of right and wrong, and our persistent failure to live up to our own standards. While he does discuss how Christianity reshapes character and moral life, his primary goal is to argue that it’s not only useful to everyday life, but also true.

Crime and Punishment

Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1866.

Crime and Punishment is the best depiction of what it’s like living inside someone else’s head. The novel follows a down-and-out former university student Rodion Raskolnikov as he deals with an unfortunate situation, makes some regrettable choices to pull himself up, and how he deals with the aftermath of the hole he creates.

Very little “happens” in the book. Past the first several chapters and the commitment of the titular “crime,” for the remaining hundreds of pages we get to live through Raskolnikov’s mental and emotional anguish as he wrestles with, both to himself and to others, what he’s done. He’s wracked with intense levels of disbelief and guilt, borderline insanity, psychosomatic illness, intense fever. We watch his mental state deteriorate, in tension between hiding what he’s done and giving himself up, to his friends, family, and the authorities.

Raskolnikov is a youth consumed with ideas. He’s an idealistic believer in the “Great Man” theory: that the world is moved by extraordinary individuals, and that we permit the extraordinary among us to morally transgress in pursuit of higher purpose. Dangerously, though, he also believes that he may be one of these Great Men, and rationalizes his way to his actions from a position of desperation, poverty, and resentment. He wavers between an overconfident arrogance about a position in the world he feels he deserves, and a self-loathing rooted in his subconscious understanding that he’s just a man. In one scene he can be tender and compassionate, in the next coldly rational and abstract. He generously gives all of his money to the consumptive widow of a man he briefly meets early in the story. Yet throughout, he fancies himself a Great Man like Napoleon, who can violate moral fabric in the micro to serve some greater good in the macro. He justifies the pawnbroker’s murder to himself as ridding the world of “a louse, sucking the life out of the poor.”

Ultimately something in his subconscious doesn’t accept his own excuses to himself. Try as he might to talk himself into his abstractions, his inner struggle between his philosophical rationalization and the deep moral wrongness he knows he’s committed manifests as an unsustainable, chest-caving guilt.

In this age of the rational, where we look everywhere for scientific, legible explanations for everything (and even worse, justifications), Raskolnikov’s twisting internal pain reminds us that even if we can create a justification for our actions, we still might slam into an invisible moral foundation. Hopefully we all maintain that rigid foundation that generates guilt and shame in the presence of rationalizing our wrongs.

Even though it’s a 150 year old book, I won’t spoil the ending. Suffice it to say that it’s a satisfying end to a slow, rich burn.

Notes Towards the Definition of Culture

T.S. Eliot, 1948.

When we talk about culture, we’re often referring to different things. Often it’s the simple things like art, opera, and cuisine. Eliot is interested in deeper definition. The way societal roots grow through millions of small actions by groups and individuals over a long period of time, and how those roots support varied, interesting outputs in the societies above them. Strong foundations developed through bottom-up cultural forces are stronger and more resilient than any top-down plan. His definition of culture sits at a deep level in the pace layers stack.

This extended essay is Eliot’s attempt to come up with a concrete way of defining culture that has more utility than the way it’s bandied about most of the time, the way we might call a person more refined than others (”look how cultured he is”), or to describe the patterns of small groups or neighborhoods. He aims to figure out what culture means for whole societies.

He argues that culture is not a detachable segment of society but an organic whole. It’s the accumulated patterns of belief, custom, work, art, and everyday life that grow over generations. Culture can’t be rationally designed or imposed without distortion; it depends on historical continuity and tacit inheritance, not deliberate planning. Eliot rejects the modern tendency to treat culture as something that can be designed through education policy, state programs, or mass access alone, insisting instead that culture emerges only where ways of life are stable enough to be handed down and slowly refined.

Culture exists only where people feel bound to what came before and responsible for what comes after. He positions the family the main vessel of cultural continuity, and calls culture “a conversation between the living, the dead, and the unborn:

But when I speak of the family, I have in mind a bond which embraces a longer period of time than this: a piety towards the dead, however obscure, and a solicitude for the unborn, however remote. Unless this reverence for past and future is cultivated in the home, it can never be more than a verbal convention in the community. Such an interest in the past is different from the vanities and pretensions of genealogy; such a responsibility for the future is different from that of the builder of social programs.

The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left

Yuval Levin, 2013.

It may be surprising to learn that one of the greatest supporters of the American cause in the Revolution wasn’t an American. In fact, it wasn’t even a Frenchman, allies of the Americans against the British. It was an Irish-born English politician named Edmund Burke.

When it comes to governing a people, we tend to focus on ends rather than means. What policy are you pursuing? What are the appropriate rules and laws? The decade-long disagreement between Burke and Thomas Paine demonstrated that question that should have primacy is about means. How should we go about the business of governing ourselves? What is the right strategy to implement the policies that pursue our goals?

Burke and Paine largely agreed on the merits of the American project, its goals and objectives, which is what makes their later profound disagreements so interesting. When revolution started to simmer in France by the mid-1780s, Burke and Paine were aligned on the goals, yet not the tactics. As the revolution intensified and became ever-more violent, the rift between the two widened to a chasm.

In Burke’s view, the prime directive of society is retention of what works first and foremost. An evolutionary, institution-first approach. From his vantage, it was most important to preserve the functions of institutions, even if some of those functions were corrupted and in need of reform. Tradition, by Burke’s lights, held a rich storehouse of difficult-to-replace, hard-earned knowledge. The revolutionaries, in their zeal to rip apart and rebuild French society root and branch, risked throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Paine’s angle favored reasoning in the abstract, focused on principles for their own sake irrespective of the reality on the ground. If X is “right,” we should do X. In his view, we could overhaul society from first principles and create its ideal replacement according to what should be, even if we’d have to break some eggs to get there.

The revolution in France played out much closer to Paine’s worldview. And it turned out Orwell’s line was appropriate, in response to breaking some eggs to make an omelette: “Where’s the omelette?” The revolution sought a utopian objective that its greenfield means couldn’t achieve. A few years later the nation plunged into Napoleon’s totalitarian reign.

Paine and Burke exemplified Sowell’s constrained and unconstrained visions better than just about any two contemporaries. And even though Levin (and I) hew close to a Burkean line of thinking, he makes a strong, defensible case for Paine’s point of view, and gives him plenty of credit for his earlier role in the American project.

The Roots of American Order

Russell Kirk, 1974.

The American flavor of societal order is a fascinating thing. 250 years ago we kicked off this experiment in freedom and self-government, and achieved a remarkable degree of constitutional stability, while preserving a rich cultural fabric.

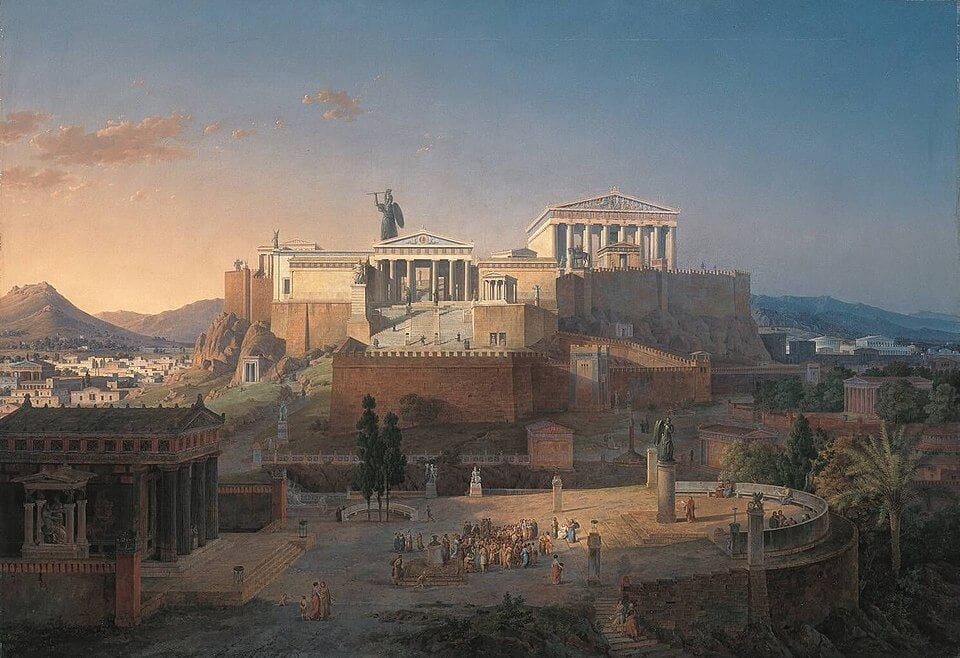

Kirk’s project is to trace where we get the ingredients for this stew. Many historians would go back to Locke, Hume, and Montesquieu, and Kirk gives them their credit, too. But he traces even those roots deeper, all the way back to Jerusalem, Athens, Rome, and medieval England. Hebrew religious doctrine provided a grounded moral foundation. Ancient Greek philosophy developed into a respect for civic virtue, reason, and justice. The Roman Republic added tested, durable concepts of citizenship and political Infrastructure. And the English system gives us common law practices of building legal frameworks on empirical, locally-derived experience.

The book is a detailed investigation of how these sources have combined and evolved into the American framework. It’s all interconnected going back over two millennia, mixed and intergenerational: a fundamentally “Burkean” story. Our system that combined freedom, restraint on power, and error correction owes its existence to an inherited tradition of what’s worked over the centuries in western civilization, preserving the good while making gradual progress. From ancient Judaea through to the American founding, it didn’t take any big swings at Utopianism to get where we are (only the correction of failed ones). America’s order endures, while countless other totalitarian attempts at order have fallen into the dustbin of history.

Frankenstein

Mary Shelley, 1818.

Even with this as assigned reading in high school, I didn’t even crack it open back then. Another case of missing out big time on a fascinating read. There are so many classic works that are just silly to hand to young people and expect them to appreciate.

Frankenstein is one that’s much more cerebral and psychological than the impression left by popular culture would have you believe. The high school sophomore picks it up expecting a scary monster story, and while it is one to a degree, it’s much more a psychological thriller than anything else. After introducing Victor’s education and interest in scientific progress, the creature’s creation scene passes in a flash. In cinema it’s become a model for many a terrifying scene. But in the novel, it’s over in a couple of paragraphs. The science behind Victor’s work is not even explained one iota, which I actually appreciate. If this was published in 2025, a third of the book would be about the scientific process of Reanimation Science.

It’s a story about so many things other than “horror” (the section where you might find it on the shelf): the overreach of unrestrained rationalism, responsibility, loneliness and isolation, the limits of human knowledge, revenge.

If you’ve never read it, or it’s been a long while, I highly recommend.

Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity

Paul Kingsnorth, 2025.

Kingsnorth sets out to diagnose what’s wrong with the culture in 2025. He describes what he refers to as “the machine”: a ceaseless, humanless system (that humans are participants in) driven by and endless need for growth, centralization, homogenization, and abstraction.

If you find something in works like Seeing Like a State and have an anti-tech streak, there’s an argument here you’ll have sympathy for.

But I’m of mixed mind about this book. I agree with some of the diagnosis about the endless need to make everything decodable and legible, centralized, plannable, engineerable. But I get off the bus when Kingsnorth gets into his proposed answers — or at least his suggestion of where a fix might come from. He starts by making statements I agree with, that the problem is a cultural one, of human choices. If we don’t like Instagram, state surveillance, or never ending industrial growth, we should start valuing what has meaning closer to home. We should make different choices as individuals.

But then he goes hammer-and-tongs after everything tech and capitalism writ large. Those things are by no means perfect or in no need of reform. But they’re downstream of individual choice. We have agency, and can make different decisions. The free market is nothing more than the sum total of individual action. If we’ve got a problem with capitalism’s outcomes, we’ve got nowhere to look for blame but inward.

Kingsnorth is onto something here about cultural rot. Our respect for traditions, our elders, for meaning — we’ve allowed all these things to erode away through neglect.