Two roads to longevity

Ford, Rolls-Royce, and two different philosophies on building things that last

In Stewart Brand’s new book Maintenance: Of Everything, there’s a section on the early days of the auto industry. He chronicles several of the key innovations and technologies that converged in the early 20th century to produce a boom in production, transforming culture, cities, economies, and so much more as a result.

Two of the early pioneers in auto production harnessed many of the same advances — in precision engineering, machining, tooling, manufacturing techniques — yet came at the problem with wildly different philosophies of production.

At a time when the first “horseless carriages” were unreliable, difficult to start, and even harder to keep running, Henry Royce developed a complex method for building extremely reliable, performant, and appropriately expensive vehicles. Rolls-Royce’s famous Silver Ghost was a marvel of human ingenuity and craftsmanship. Each part meticulously machined to aggressive tolerances, and hand-crafted one at a time. They were things of beauty, but they were also neither accessible (a couple hundred-thousand in today’s dollars) or plentiful:

Superb performance and reliability were designed into Rolls-Royces through how they were made. Each Silver Ghost was manufactured as a bespoke, unique vehicle, meticulously crafted by a dedicated team led by Henry Royce, the partner responsible for engineering. The experts assembling the car were armed, according to journalist Simon Winchester’s 2018 book The Perfectionists, with “their loupes on lanyards their slide rules, micrometers, calipers, verniers, and pressure gauges.”

(Brand, Maintenance, p. 56)

For the time, in these early days of pre-mass manufacturing, the Rolls-Royce approach made sense for a certain audience. The customers that could afford them loved them: rock-solid dependability, steady and quiet (hence the name), and a nearly hands-off monument of engineering. Something like 1,500 of them are still around today over a century later, of ~7,800 produced. 20% survival over that long a haul is unprecedented for just about anything ever produced, then or certainly since.

While Royce made every Ghost a hand-crafted icon of extreme precision, Henry Ford ran with a different philosophy. He became a legend not only for his application of the assembly line, and interchangeable precision parts, but also his belief in reach. He wanted a design and manufacturing methodology that wouldn’t put an upper limit on production volume. While Rolls topped out at about 2 Ghosts per day out of the factory, Ford’s Model T could hit 10,000 per day at peak production. Royce made it his mission to satisfy his few customers for life. Ford wanted to build “the Universal Car,” one for every driveway.

High road, low road

One thing that jumped out to me reading about this history is its parallel to another Brandian idea from one of my favorite books, How Buildings Learn. There he describes a framework for thinking about buildings in two broad categories: Low Road and High Road buildings.

Low Road buildings are characterized by their flexibility and adaptability to change, designed with simple, robust components that can be easily modified or replaced without compromising the overall structure. They allow incremental, organic evolution over time without requiring major interventions or extensive renovations.

In contrast, High Road buildings are less adaptable and have a more fixed design, often constructed with specialized and intricate systems that are difficult to modify or update. They tend to exhibit a higher level of architectural ambition and style. Their rigidity makes them less resilient to change and less capable of responding to evolving user demands.

Low road buildings are flexible, scrappy. Soho’s famous cast-iron buildings from the turn of the century fit this mold. They were originally used as manufacturing houses, for things like textile production or print shops. As those industries left the city, buildings were neglected and their values dropped, until artists and creatives started renting out the huge spaces as loft studios for living and working, throwing in partitions and kitchens as needed. The openness and robustness let them adapt to changing user preferences over the course of the century, from manufacturing to artist lofts to galleries to tech offices and luxury condos of today. With the low road, our buildings adapt to our evolving needs.

The high road is about preordained purpose: buildings designed with intent. Cathedrals are among the best examples. We don’t build them to adapt to their occupants, like office buildings to be leased to the highest-paying industry. Cathedrals are built to achieve religious ends, as places of worship that should stay places of worship. The stained glass, soaring vaults, the nave-and-altar orientation — all of it conspires to produce a specific experience, a specific use. High road buildings resist modification because modification would defeat the whole enterprise. You don’t retrofit a cathedral into an open floorplan office concept. You maintain it, restore it, honor it. The building endures because it’s worthy of the extraordinary effort required to keep it exactly as it is. With a high road building, we adapt to its designed intent. Our behavior adjusts to fit its purpose.

Royce’s Silver Ghosts were objects of this kind of sacred refinement. His cars were so meticulously assembled that popping the hood and tinkering without the requisite expertise would cause damage. You didn’t modify a Rolls-Royce to go off-road. You carefully maintained it. You paid homage to it through the ritual of care and attention. And if you did, the thing would run for a hundred years.

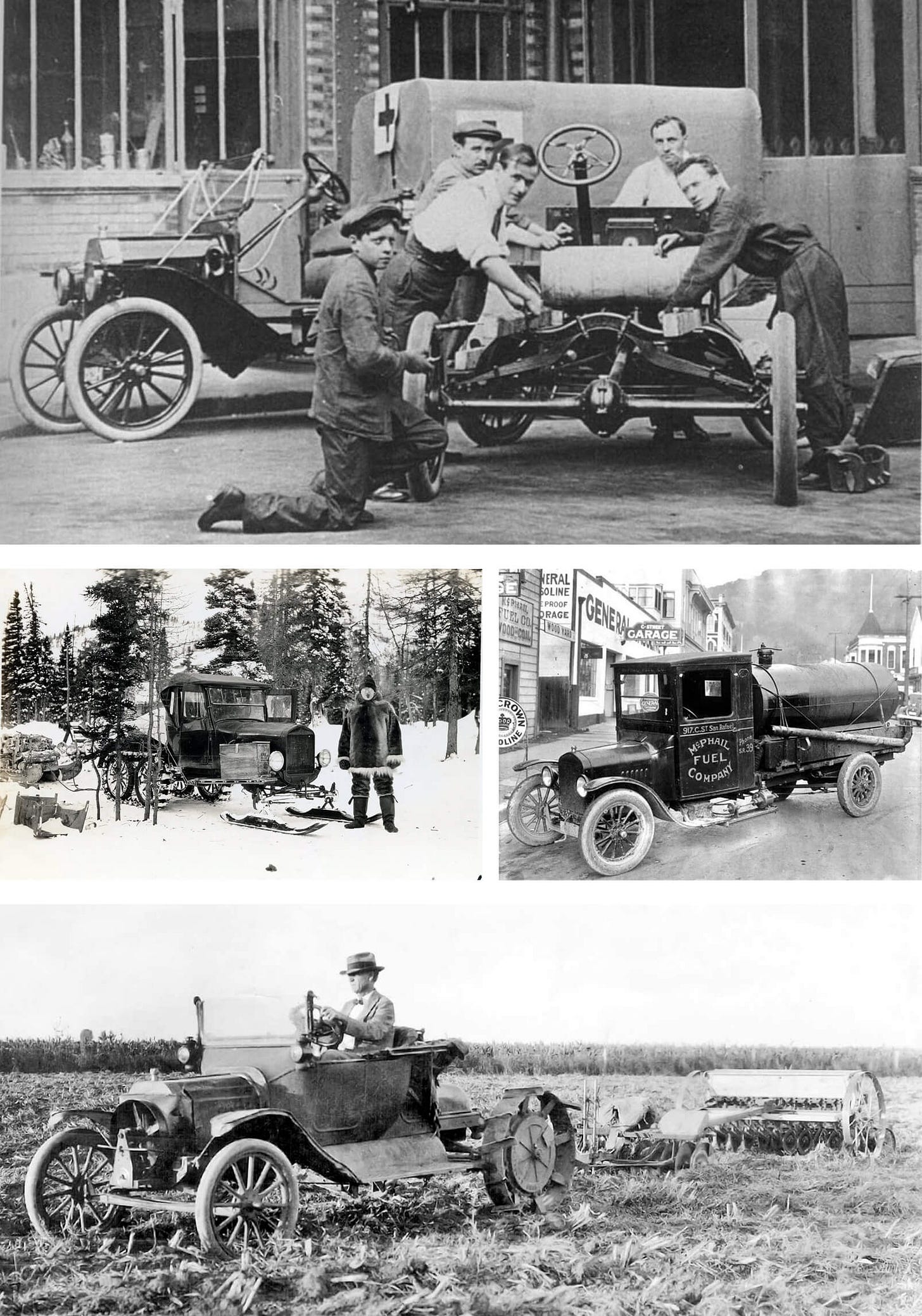

On the other hand, Model T’s were famously “hackable.” The simple, modular design composed of interchangeable parts, its low cost accessibility, its ubiquity, all these factors contributed to the wild west of use cases found for Ford’s everyman automobile.

There were so many Model Ts that the specialized knowledge needed to keep them running became common knowledge. Anyone who tried to customize a Silver Ghost would probably screw up its tightly integrated perfection, so no one did. Every Model T, on the other hand, required some customization just to function well, and that inspired owners to devise all manner of new features and functions. A Rolls-Royce, impressive as it was, had just one use. When Ford put the power to make changes in the hands of his millions of customers, the Model T evolved rapidly in all directions and was put to countless uses.

(Brand, Maintenance, p. 62)

The T’s broke down regularly, encountered problems with routine frequency. But because they were everywhere, so were their parts. Their simplicity meant you could take them apart with basic tools. You could fix them on the roadside. And when drivers had a special need on the farm, or to haul cargo, or to drive on the ice, they modified the cars to fit their needs. Low road vehicles adapt to their users.

Two philosophies of longevity

What I find compelling about all this is two divergent approaches to longevity. We have polar opposite philosophies of design and construction that each is capable of producing things that well outlast their owners, and this applies to buildings, vehicles, and anything else we bring into our lives.

The Rolls endured through reliability. The Model T endured through repairability.

One inspired the devotion of its owner. The other devoted itself to its owner.

Beneath these differences, the two philosophies produce durability through honesty about what they are.

There’s another interesting detail worth noting. In both the architectural and automotive cases, the low road examples achieved something their creators never intended. Nobody at MIT planned for Building 20 — a plywood and timber “temporary” structure — to become a legendary incubator of science. Nobody in nineteenth-century New York designed factory lofts to become apartments. And Ford, for all his vision, didn’t set out to build a platform for improvised snowmobiles.

The magic of the low road is that its virtues are emergent. Ford’s mission was volume — get cars to as many people as possible. The assembly line, the interchangeable parts, the simplicity of design: all of these served that mission. But those same choices, that same lineage, produced a secondary gift: radical adaptability. The repairability and the hackability were byproducts of the manufacturing philosophy, not its objectives.

Making a considered choice

It strikes me that today’s cars and buildings often live in this no-man’s land, a sort of purgatory between the low and the high, taking on aspects of each but the benefits of neither. We throw up boring buildings stuck in the middle. They inherit the low road’s cheap, modularity of construction without its genuine flexibility. And they bring the high road’s rigidity without any of its grandeur or earned respect.

We do the same in the auto industry. Modern cars are a marvel of engineering, don’t get me wrong. But we use low cost, mass-manufacturing techniques, without any of the low road’s maintainability. Neither are they worthy of reverence. That 2004 Nissan Altima can’t be easily repaired at home or on the roadside, but neither does it command the worthiness of a full restoration.

This design space limbo leaves us rudderless when it comes to longevity. We don’t build things worthy of being maintained, and we couldn’t do the maintenance if we wanted to.

This is perhaps the deepest lesson of Brand’s framework. You don’t have to choose low road or high road based on which one is “better.” Both Ford and Royce built legendary businesses. The Model T and the Silver Ghost both endured into the history books. The important thing is to choose — to commit to a philosophy honestly rather than drifting into the no-man’s land where cheap construction meets inflexible design.

Then all we do is inherit the costs of both and the soul of neither.