MIT's Building 20: a Masterpiece of Utility

Res Extensa #37 :: On low vs. high road design, How Buildings Learn, and crafting buildings fit for purpose

"Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings."

-Jane Jacobs

When you enter a building, you get a sense for its "aliveness", the vitality of the space. Some feel vibrant, energetic, purposeful. Others feel dead, empty, disused, disrespected. Certain spaces feel organically well used — the souks of Istanbul, an artist's Soho loft, the cavernous factory-turned-food hall that's bustling with people and live music. Others, designed for specific uses (sometimes even still brand new) are empty husks, overbuilt, abused, or even unoccupied — the fixed office layout with an empty open atrium, the shopping mall with no foot traffic, the office building with too many windows that cooks you in the afternoon sun.

Great buildings have fitness. Not in the health sense, but the evolutionary one: as in fit for their particular use. Adapted well to what humans want to do with them. A constant in the world of buildings is that our uses for them change over time. Therefore, the most fit buildings will evolve with us.

In his 1994 book How Buildings Learn, Stewart Brand explores this idea: how buildings adapt to humans, and how we modify them to our own ends. The book's subtitle states Brand's interest: what happens after they're built. Tracking the progression of changes to buildings over time, the book is chock full of examples of buildings adapting to their environments.

One of his central ideas is the contrast between what he calls "Low Road" and "High Road" buildings:

Low Road buildings are characterized by their flexibility and adaptability to change, designed with simple, robust components that can be easily modified or replaced without compromising the overall structure. They allow incremental, organic evolution over time without requiring major interventions or extensive renovations.

In contrast High Road buildings are less adaptable and have a more fixed design, often constructed with specialized and intricate systems that are difficult to modify or update. They tend to exhibit a higher level of architectural ambition and style. Their rigidity makes them less resilient to change and less capable of responding to evolving user demands.

So on the low road, buildings adapt to their users. On the high road, the users adapt to their buildings. An open-floor WeWork coworking space, versus St. Paul's Cathedral.

Building 20

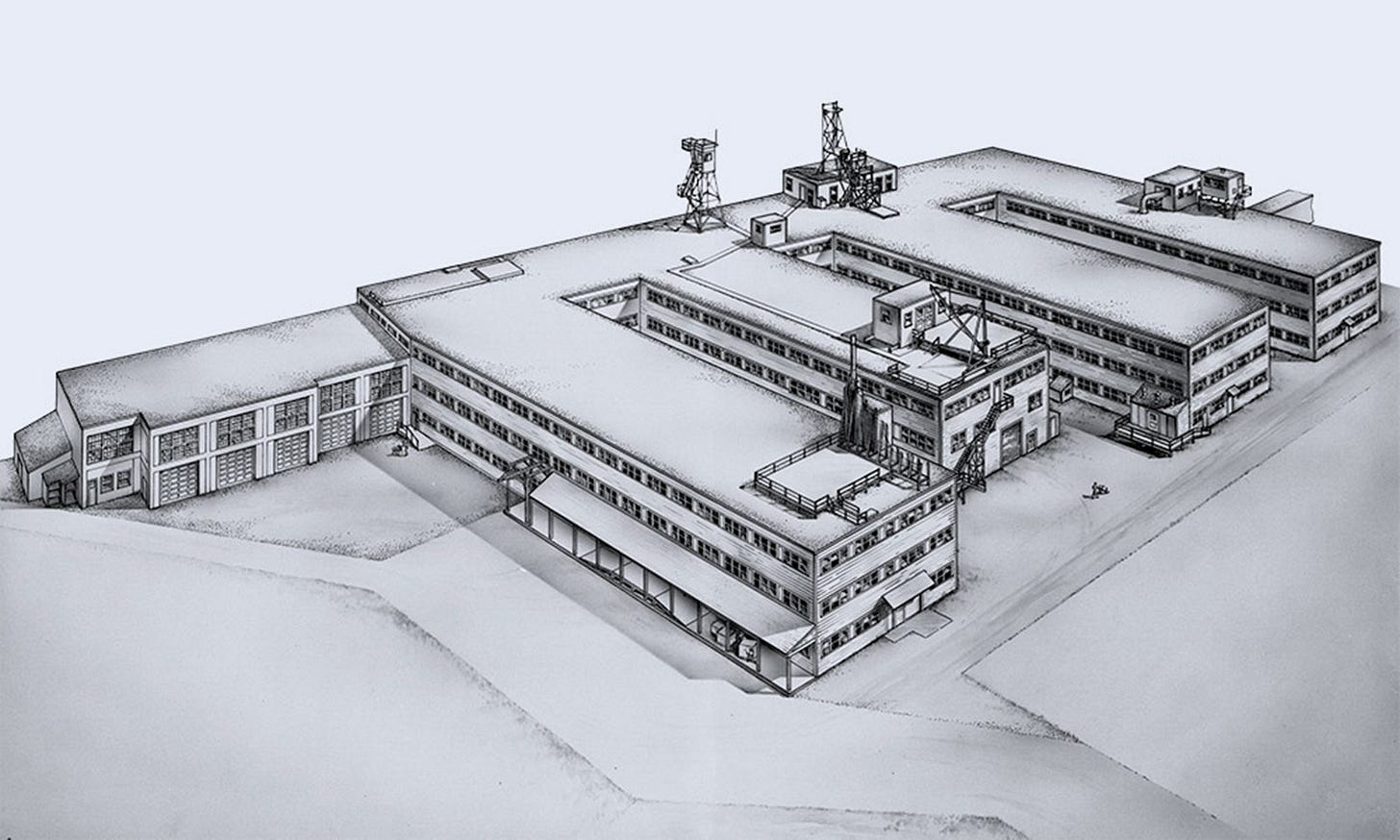

An emblematic example of the low road done best was built on the campus of MIT to support R&D during World War II. The Institute's Building 20 was 250,000 square feet, with three low-slung stories, built in timber frame construction (the war effort commanded the steel supply). It went up at lightning pace to house the Radiation Lab, the euphemistically-named research laboratory working on microwave and radar technology. The Rad Lab was booming, outgrowing all of its existing space across 3 other buildings.

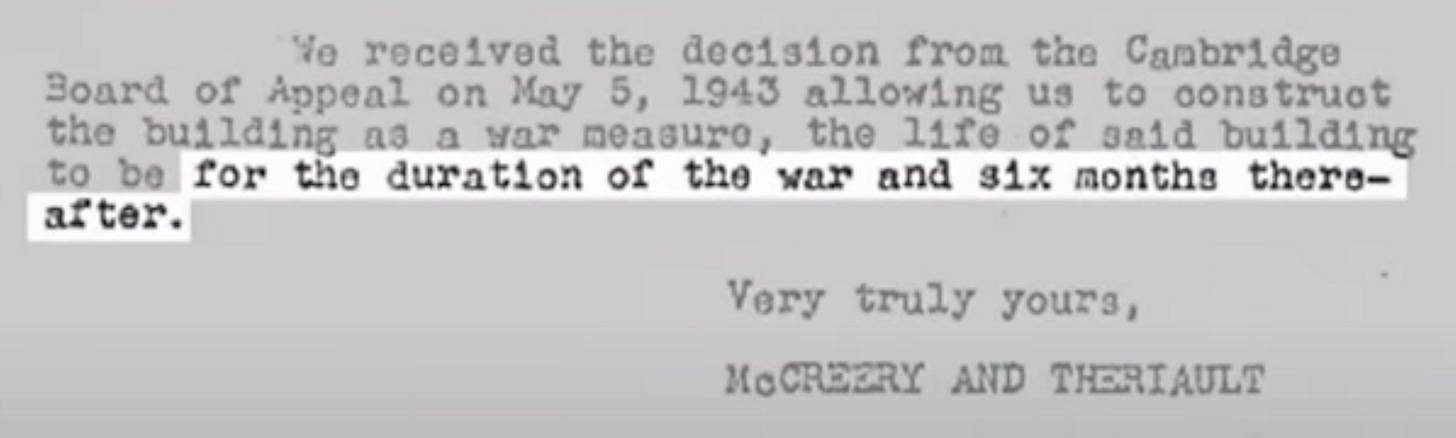

The order for Building 20 authorized its slapdash wood construction because it was intended to be temporary, a status which it held for 50+ years. Its occupants called it the "Plywood Palace".

This eulogy for the building speaks to its impact:

The building was created out of wartime necessity, but it soon mushroomed from a shelter for a handful of specialists to a home for almost 4,000 researchers in 20 disciplines. At one time, more than 20 percent of the physicists in the United States (including nine Nobel Prize winners) had worked in that building, said Dr. Theodore Saad, an original member of the Radiation Laboratory at MIT.

The flat layout of the building made for constant chance encounters in the hallways. Vertical buildings create rigid boundaries, since floors and stairs are harder barriers, so the horizontal footprint caused people to run into dozens of others throughout a typical day. From the air, it looked like an oblique letter E (with a little extra E), and these wings forced people to walk the halls:

A researcher in one office would hear a sound from below through the thin wood floors, and curiously trot down the stairwell to see what was going on. Neighbors heard each other through the walls and popped in to observe work going on in other fields. If two people a few rooms apart wanted to collaborate — if machines needed to be interconnected, plumbing run, cables strung between rooms — no need to call physical plant. Just drill a hole through the wall, or run cables along the open hallway ceilings. No permission required. Some folks even busted through the walls into the courtyards between the wings and extended their spaces with sheds or other outdoor facilities they needed. Even the vertical space was modifiable. Physicist Jerrold Zacharias developed the first atomic clock in Building 20, and to do so he had to blow through and connect all three floors to house the massive cylindrical structure of his cesium-beam clock .

The place was moldable like modeling clay, conforming to the needs of its people, rather than forcing a particular mode of work on them. And as a result, the list of developments that took place there reads like a Hall of Fame of scientific research: Amar Bose developed his loudspeaker technology there. Noam Chomsky pioneered modern linguistics in a dirty office. The PDP-1 was built there, one of the first minicomputers. It spawned Bolt, Beranek, and Newman, the firm that would go on to build the earliest iteration of the ARPANET, the proto-internet.

From its storied history, you can see what happens when a building has lock-step "fitness" to its intended use. The open, modifiable layout made it a den of idea cross-pollination: just what you need for the sort of creative, divergent thinking necessary on the frontiers of R&D.

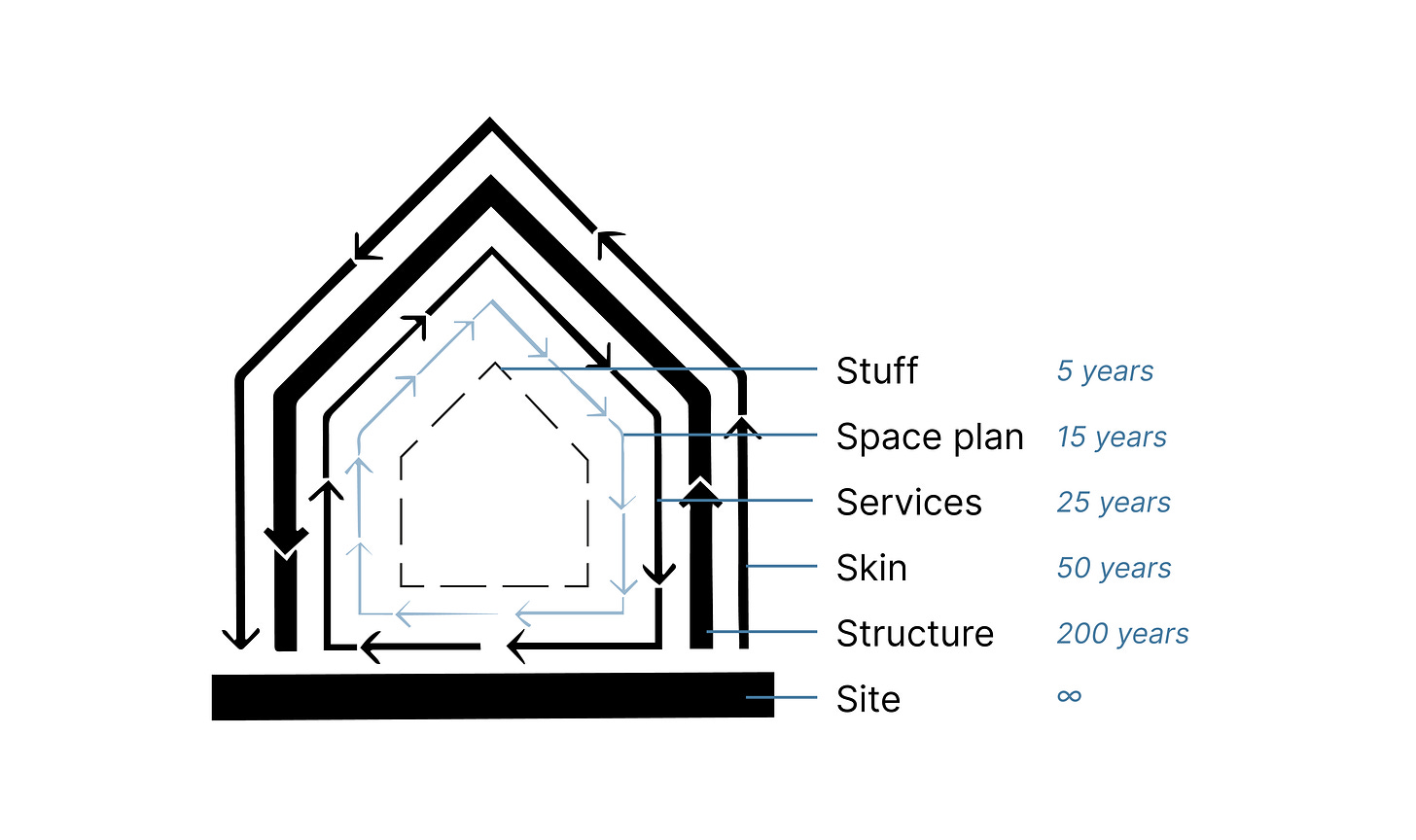

Shearing layers

Architect Frank Duffy coined the term "shearing layers" to describe a mental model for a building's systems and components, nested in independently changing, hierarchical levels, which Brand expanded from the original four to an alliterative six. Each layer serves a purpose, is variably adaptable, and evolves on its own time scale:

The site is where it is: a permanent, unchangeable attribute. The structure is the most expensive to modify, so it's rarely done; often cheaper to tear down and start over. But each other layer is modifiable, more or less so depending on the building's design. In many modern buildings, the services layer is incredibly hard to change, or at least has a hard time accommodating the progress of technology. 150 years ago, buildings didn't need to provide space for mechanicals: HVAC, cable, ethernet. It's hard to design with the unforeseeable in mind.

What Building 20 did so well was create a malleable canvas with the maximum level of elasticity in its layers. Even the usually-rigid Structure layer was fair game to the hackers in 20. Just about the only thing that wasn't changed to fit the work going on inside was its location.

Designed spaces vs. open canvasses

The design of Building 20 came together under duress, with the growing Rad Lab already busting the seams of all its other buildings on the campus. So the architect didn't overthink the plan. They just slapped together a utilitarian space to jam with scientists. The war wasn't going to wait. And even though its construction methods violated building codes, they got special approval for calling it "temporary".

This sort of "bottoms-up", "let the users decide" design approach — almost undesigned, actually — allowed for permissionless adaptation. When the users needed something different, they made it happen.

I find an interesting parallel here to the ideas James Scott proposes in Seeing Like a State (which we covered back in RE #4): a top-down, central planning-style of design can't effectively predict the diversity of user needs. It turns out, contra to the "expert architect", that the users know best what they need from their space. And often even they don't know their future needs on the day they move in.

Building 20 was demolished in the late 90s, making way for a new Frank Gehry-designed deconstructionist eyesore, the Stata Center. It didn't take long for some of the occupants of the former building to level their critiques:

When my structures class toured the site during the construction of Frank Gehry FAIA’s Stata Center, which replaced Building 20, we marveled at the massive concrete transfer beams, hanging columns, and other structural acrobatics. This had been designed as a highly specific space where the needs of the occupants had been studied, categorized, and then fit into a master scheme; where the spectacle of architecture would be the organizing principle; and where the occupants would be part of the spectacle. Visiting the occupied building a few years later, I found it hard to imagine the architecture adapting easily to needs that may not have been considered.

The scourge of the "artist architect" is an entirely separate tangent, fodder for some future issue. Some architects have a tendency to approach design as if they're building a monument to their design genius, and not a space intended for unglamorous function. It's a topic Brand goes into at length in How Buildings Learn. He calls it "Magazine Architecture": design for photographs, not users.

I love this quote from Dr. Jerome Lettvin, who spent years in Building 20 during the 50s:

Building 20, said Morris Halle, a linguist who spent decades inside the wooden structure, was cheap. It was not designed at all, just built. And that was what gave those who worked in the building the freedom to change their space as they saw fit. But in the new building, people will not even be able to open the windows.

“Can you believe it?” Dr. Lettvin said. “Too expensive now to make windows that open.”

When to design, when to get out of the way

Buildings are typically designed and built with the intent of lasting decades. For high road "institutional" structures – think churches, civic buildings (city halls, capitols), or stadiums — they're designed with an express purpose that a designer understands. A reliable, predictable use case that'll still be its purpose decades on. But most buildings aren't high road in their usage. They're utilitarian, to give people a place to live and work. Office buildings, warehouses, university halls, retail spaces. During design, architects can't possibly know what sort of space will be in demand 50 years on. Often the design assumes an unchanging use case. And this doesn't mean low road is the superior model; it's about creating buildings that are fit-for-purpose.

Sometimes what we need to do as designers is get out of the way, to create a canvas with a "low floor, wide walls, and high ceiling". Let the users take control and find the right fitness function through adaptation. Build what works, tear down what doesn't.

If you’re interesed in more, MIT created this excellent mini documentary on the building, which I highly recommend.