Escape the algorithm

A return to active vs. passive consumption

The art of discovery in culture is a dying one. There was a time when finding new music, books, products, or works of art was a skill you had to cultivate. Finding new and interesting things was an effortful activity that required your attention. People became known for their opinions — you took recommendations from a particular reviewer because you had a mental model of their taste in culture. You relied on Roger Ebert or SPIN magazine to tell you what was worthwhile.

If you were a fan of science fiction novels, there was no Amazon to tell you "Others also enjoy Vernor Vinge". If you found you liked Mogwai, no Spotify algorithm was there to queue you a playlist of Tortoise and Explosions in the Sky.

If you were in the market for something new and adjacent, you either went to expert curators, or you had to do the work.

Internet media now leaves nothing to the consumer: new content is pushed to you by algorithmic curation machine, not pulled by you through browsing and digging.

In the old days, our "algorithms" were friends, MTV, the radio, the record store, Blockbuster. Our engagement with recommendations was receive-only. What we liked or disliked did little to modify future recommendations; what feedback loop there was between our preferences and what got promoted to us was extremely indirect (focus groups, box office receipts, record sales, letters to the editor). There were measurements of feedback, but none of these loops were personal. The best we could do was the promotional endcap, curated by the employees' tastes in genre.1

As all media distribution has moved online, every service now centrally features the feed, algorithm, Discover tab, or For You page. Exploration is no longer an active, engaged activity. The default is a passive delivery of things right to your eyes and ears.

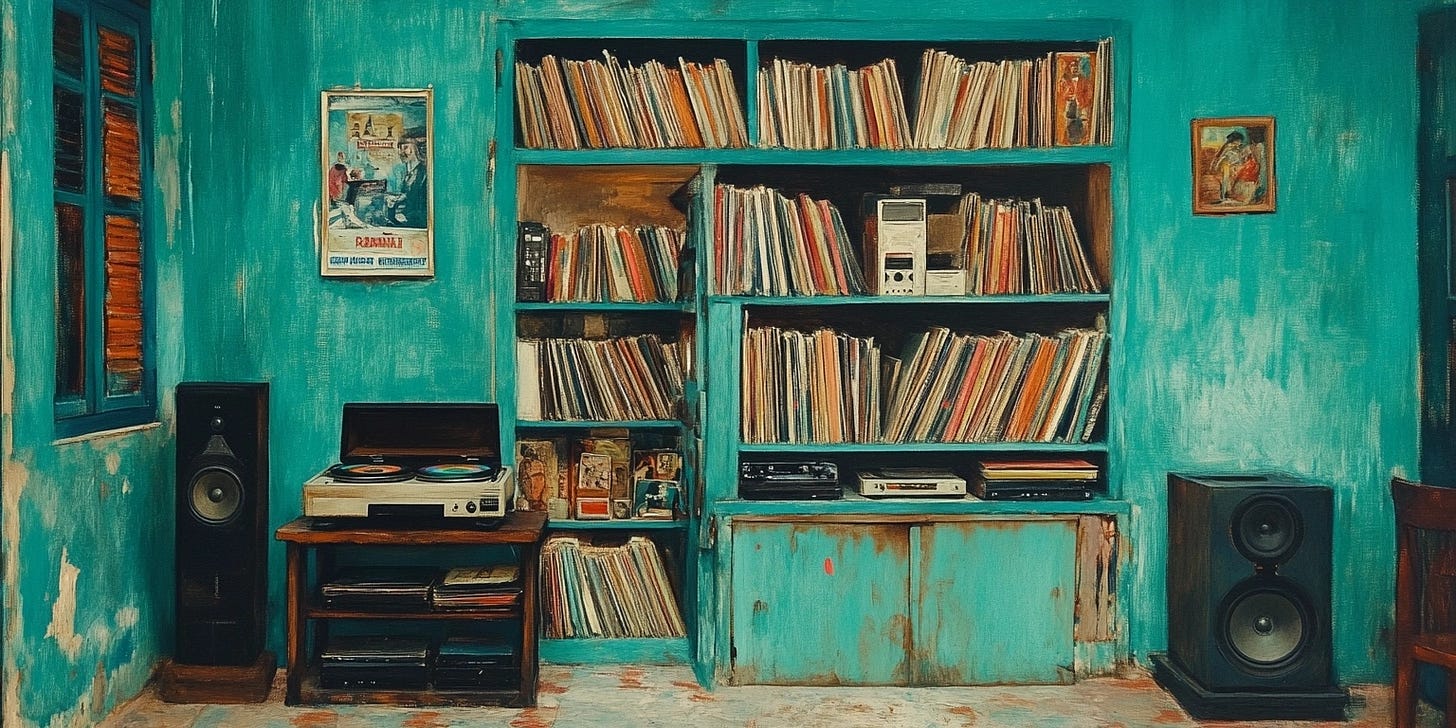

It leaves me wanting a return to the intentionality of opening up my iTunes library to play a specific album, rather than letting YouTube or Spotify choose for me.

On his channel Digging the Greats, musician Brandon Shaw went on a journey trying to "go analog" from his digital, algorithm-centered life. He started an experiment to listen to music only on an iPod for 30 days (yes, a refurb'd 15 year old device) and get his music recommendations from people directly. What started as a music experiment eventually led to a multipart series pulling back from Instagram, X, Spotify, and others — moving to a point-and-shoot camera, reading physical books, typing on a typewriter. I mean, he went all the way. The whole series is fantastic, but start with part 1:

There's something compelling about paring back on the glut of media consumption channels we all have at our fingertips, like Brandon did. Right after watching, I went and deleted probably 100 apps from my phone. Cruft like that just builds up over time. These weren't even things I often use, but each new app expands the surface area of potential distraction. I'm already diligent about preventing apps from notifications, opting out of the continuous buzzing phone, but there's something compelling about taking it further. About regaining agency over what we consume: seeking out specific things to engage with more deeply rather than waiting for what's next in the scrolling feed.

I'm not interested in the full-bore, low-tech waldenponding experience Brandon was going for. I'm completely okay with (and enjoy) recommendation engines and the access to the world's media these products afford. The problem is when. Spotify and Instagram and TikTok are algo-first — right when you open them up, they want your attention on what they want it on.

I want to regain control over my attention, not just consume whats shoveled onto the screen.

Recently Ted Gioia published his 12-Month Immersive Course in Humanities, with week-by-week recommendations of great works: books, poetry, music, art. It got me thinking about being more intentional about my consumption. Like any 21st century connected citizen, I'm awash in music, TV, and things to read. The surfeit of content on the internet in some ways demands algorithms. How else to navigate the overwhelming volume of stuff than with an assistant to show you around? Even in a store like Tower Records in 1995, there were limits to what you'd even find, let alone what you could afford. But Spotify has effectively no outer edge.

Algorithms have a place, of course. Plenty of music I like or YouTube channels I subscribe to were found with the help of Big Algorithm2. It's a marvel of modern technology and mass media that we can find an obscure Japanese woodworker building furniture, or learn that we like balkan folk music.

But that makes it too easy to hand your selectivity — your tastemaking — over to a tech titan to sort out. I don't want that. I'm interested in going deeper with specific things I've purposefully chosen.

I just finished reading Gioia's book How to Listen to Jazz, in which he makes hundreds of recommendations of the most influential and movement-forming musicians during the major phases of development of the music. From its roots in ragtime and the New Orleans sound through to fusion and neoclassical, there are hundreds of individual tunes to guide your ear to listen for specific characteristics of the definitive styles. Many of the tracks I have in my music library already, but I've also crawled YouTube to find versions (sometimes with video) of each one. And as a result I've been diving into different musicians' repertoires to listen carefully for what makes them unique. It's so much more enjoyable to study with intent than arbitrary playlists or algorithmic stations. I'm back to human-based recommendations from a careful connoisseur rather than relying on the machines.

There's a difference between what you "like" and what turns out to be gratifying, challenging, and mind-expanding. Always being pushed content that looks like everything else we've consumed before isn't the way to have your taste challenged or refined. Your mind is like a muscle that sometimes needs a workout. And too much of the engagement-tuned stuff out there is more like junk food — satisfying and addictive, but not what's good for us.

This was great! This was exactly the sort of collective promotional tactic that could surface the challenging, off-the-path, outside your comfort zone latest record that you might find you loved.

In fact, the YouTube algorithm first recommended Digging the Greats, and I'm so glad it did.