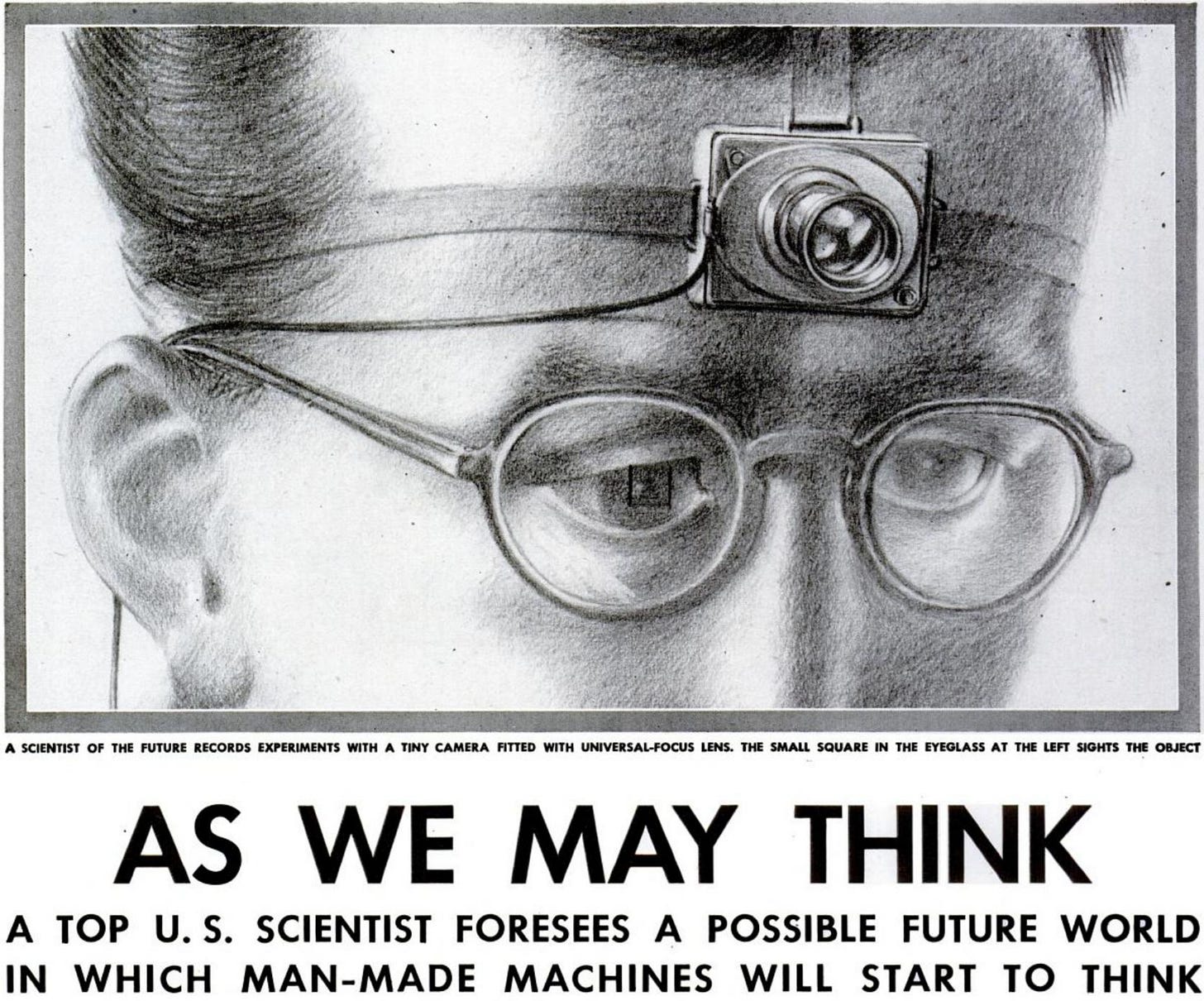

As We May Think (Internet Origins, Part 1)

Res Extensa #17 :: Vannevar Bush and the Memex, the original tool for thought

The internet pervades and powers every corner of the modern economy.

It runs parallel to and is intertwined with the development of computers. From the earliest days of computing machines, the researchers using them wanted to connect them together. At the beginning the goals were simple — publish research findings, share scarce and expensive computing resources, communicate primitively with one another. I've read a lot over the years on the history of technology and how technological progress happens. Innovation is combinatorial: one innovation enables the next, developing an interconnected web of component and predecessor technologies. Cross-country telephone lines enabled ARPANET, coordinating radar systems for air defense led to primitive networking, time-sharing led to Unix.

So I thought it'd be fun to look back on some of the pivotal developments in tech history that brought us to where we are today. This is the first post in what I intend to be an ongoing series. Enjoy.

During World War II, the US research and development complex increased manyfold, with no research institute or university left out of supporting the war effort in some way. Labs like Oak Ridge, Los Alamos, the MIT Rad Lab and many more had their origins in (mostly physicists) applying their energies to making munitions, warning systems, fuses, and even primitive proto-computers. One of the men responsible for the country's investments in what would become the computing industry was an engineer, former dean of the MIT Engineering school and president of the Carnegie Institute: Vannevar Bush.

The modern conception of the state-funded deep research laboratory was practically non-existent prior to the war. Think the ones mentioned above, or Livermore, Argonne, Berkeley, or Sandia. Scientific research, if it was being done in a deliberate way at all, was fragmented and largely a civilian exercise. During World War I, Bush experienced first-hand the struggles that researchers had coordinating work between academics, scientists, and the military. With the outbreak of a new war in Europe in 1939, and the German invasion of France in early 1940, he thought we needed an entity responsible for coordinating all of the scientific research efforts ramping up.

A few days after the Germans crossed into France from the Low Countries, Bush wrote a memo to President Roosevelt outlining a plan for an agency that would help us work smarter and faster in our research efforts, an organization that would become the NDRC, the National Defense Research Committee. Fifteen minutes after hand-delivering the one-page memo to the White House in June, he received a response written at the bottom of his document: "OK –FDR."1

Soon after the NDRC would be renamed the Office of Scientific Research and Development. Vannevar Bush made his name running OSRD, which had its mandate expanded from the mostly-military focus of NDRC, venturing into other areas, like medical treatment technology, vehicles, and, famously, the Manhattan Project. The Office's budget was in blank-check territory, with Bush reporting directly to FDR.

Bush had a long and storied career as one of the nation's leading scientific minds for decades. He was involved in research across dozens of domains — aeronautics, munitions, communications technology — most of which was in direct support of US military application. But my interest in this series is to explore the origins of the Internet and our modern usage of computer technology, and Vannevar Bush was one of the first figures responsible for igniting the 50+ years of innovation of the computer age.

As We May Think

In the middle of 1945, with the war winding down and the world in ruin after 6 years of global conflict, Bush wondered how the country might redirect the significant scientific muscle it had built up throughout the 1940s to new problems. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made this question even more salient. If we could figure out such effective and novel ways to kill one another, what could be possible if our collective brainpower was applied to peaceful activities?

This is the subject of his most famous work, the essay As We May Think, published in The Atlantic that July. Now that we understood the power of coordinated, purposeful research, the prospects for the future were staggering if we could redirect those resources to generating knowledge instead of industrial-grade killing. This bit from the editor's introduction outlines the thesis:

For years inventions have extended man's physical powers rather than the powers of his mind. Trip hammers that multiply the fists, microscopes that sharpen the eye, and engines of destruction and detection are new results, but not the end results, of modern science. Now, says Dr. Bush, instruments are at hand which, if properly developed, will give man access to and command over the inherited knowledge of the ages. The perfection of these pacific instruments should be the first objective of our scientists as they emerge from their war work. Like Emerson's famous address of 1837 on "The American Scholar," this paper by Dr. Bush calls for a new relationship between thinking man and the sum of our knowledge.

Bush wanted to improve systems for creating and expanding access to knowledge, and build technology that'd help us form collective memory. He knew that the synthesis of ever-expanding volumes of information into knowledge would be the challenge of the future.

The Memex

In the 1920s Bush had worked on the Differential Analyzer, an early device designed to solve differential equations, for the purposes of modeling electric power networks. He had the first-hand experience with the potential for what computers could do when applied to the right problems.

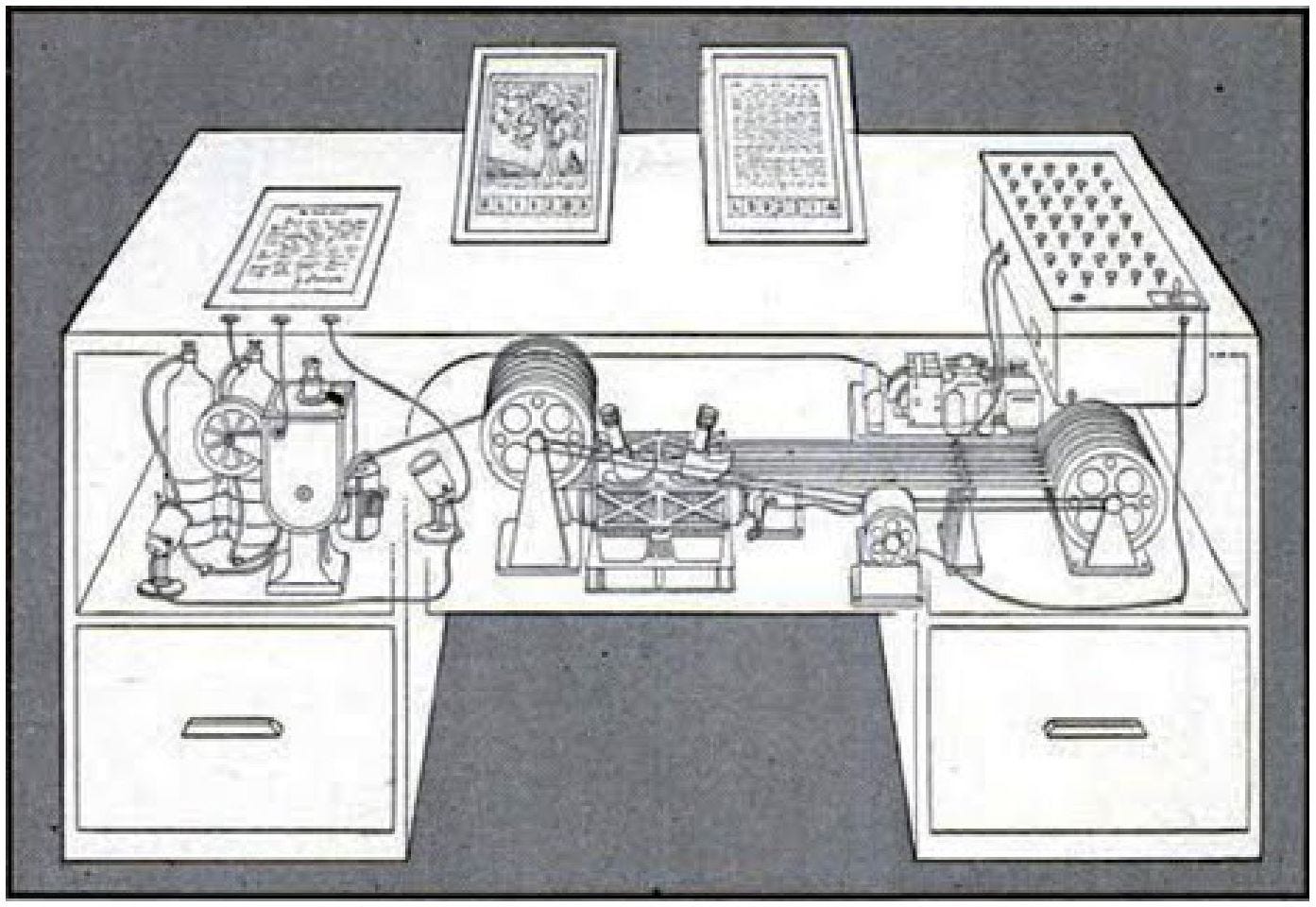

Through much of the essay, he describes a machine he calls the "memex", a desk-sized electromechanical combination of microfilm storage, photocells, coded symbols, and an associative indexing system — a workstation that would allow a researcher arms-length access to an entire research library. The lion's share of the essay is a deep dive into these various technologies, describing how they work, the current state-of-the-art for the layperson of 1945.

Many of his detailed descriptions read a little silly 80 years later, but putting it in context of the time (the first computer resembling the mainframes that would come later, the ENIAC, didn't go live until the following year), it's an amazingly prescient combination of technologies. Each sub-technology already existed then, at least in early forms, but Bush was proposing merging them into a single device intended for individual use. The computers that did exist at the time were gigantic, room-sized devices that had to be shared amongst large groups, used mostly for computation. People had used computers as adding machines, or to calculate trajectories, or for dead-reckoning navigation. But this idea that a computer could be an assistive device for human thought was new.

Microfilm and photocell technologies of the time were considered tools for librarians and archivists. But Bush's vision was that the memex could be a tool for anyone to use. The idea wasn't just to maximize storage volume or speed up filing and retreival of information. It was to rearrange so drastically how information was linked and indexed that it could change how people could think — to improve "processes of thought." He saw two decades before the beginnings of the personal computer revolution that the computer could give people superpowers for increasing knowledge.

35 years later, Steve Jobs would call the personal computer the "bicycle for the mind,” a tool for increasing mental leverage.

Hypertext

One of the most innovative and inspirational ideas from the essay was Bush's proposal for how to index and retreive information from the memex. The indexing methods of the day (many of which are still standard!) are straightforward for computers to do. Alphabetical sorting or B-trees are machine-friendly and fast, but what about how humans retrieve information?

The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain. It has other characteristics, of course; trails that are not frequently followed are prone to fade, items are not fully permanent, memory is transitory. Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

Man cannot hope fully to duplicate this mental process artificially, but he certainly ought to be able to learn from it. In minor ways he may even improve, for his records have relative permanency. The first idea, however, to be drawn from the analogy concerns selection. Selection by association, rather than indexing, may yet be mechanized. One cannot hope thus to equal the speed and flexibility with which the mind follows an associative trail, but it should be possible to beat the mind decisively in regard to the permanence and clarity of the items resurrected from storage.

As Bush identified, a human mind works differently. Our brains are associative, meaning we recall things based on their relationships to other things. With the memex, the user could establish associations between items:

When the user is building a trail, he names it, inserts the name in his code book, and taps it out on his keyboard. Before him are the two items to be joined, projected onto adjacent viewing positions. At the bottom of each there are a number of blank code spaces, and a pointer is set to indicate one of these on each item. The user taps a single key, and the items are permanently joined. In each code space appears the code word. Out of view, but also in the code space, is inserted a set of dots for photocell viewing; and on each item these dots by their positions designate the index number of the other item.

He proposed making these connections — both establishing and navigating them — interactive. The memex user could connect the items in their memex into a network of associations. Associative mappings are how researchers cite references. It's how modern wikis work. In fact, what Bush was describing was a proto-hypertext system, almost 20 years before that term was coined and before researchers tried in earnest to make a system like this exist.

But he didn't stop at the individual's personal memex machine. The real visionary move was proposing the concept of not only creating associations, but sharing them with others. Individuals could begin to cross-reference their own knowledge with that of other people. This web of trails would gradually accrete into an "ever expanding, richly-linked web of knowledge."

Inspiring the Next Generations

The memex was never built, at least as Bush originally described it. The concept was ahead of its time, and computer technology would evolve far beyond the electromechanical device capabilities that he'd outlined in his original essay. The transistor wasn't even around yet in working form; it would be the 1950s before Bell Labs's invention would find its way to commercial viability. But the impact of his work extended generations beyond the 1940s and had direct influence on some of the most important figures in the development of human computer interaction and the internet.

After reading As We May Think at the time it was published, a young Doug Engelbart was captivated by its vision of man and machine working together. In the 1960s he would go on to publish the massively influential paper Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Engelbart combined Bush's ideas with the technologies of the time and proposed a revised vision of what would be possible if humans and computers could combine forces. Go back and watch his legendary "Mother of All Demos,” when he presented his vision live. Windowing, graphic interfaces, hypertext, videoconferencing, the mouse, and more, all on display showcasing the possibilities of augmentation.

One of the legends of computer and internet research, JCR Licklider, also took inspiration from Bush in his early work with ARPA and BBN. His essay Man-Computer Symbiosis reads like a sequel to As We May Think, exploring the possibilities of using computers to extend the human capacity for thinking. He saw what could be possible if we could improve the usability of computers to the point that anyone could use them. In his mission to make computers into tools for everyone, Lick was an early pioneer of "time-sharing", a new idea at the time, the idea of using a mainframe/terminal architecture to share and make more efficient use of expensive computer hardware.

Time-sharing locally (mainframes and terminals in the same building, or nearby) eventually evolved into the idea of global time-sharing. Lick later wrote about what he called the "Intergalactic Network": a globally-accessible, hypertext-powered world computer. A global memex. The inspiration for ARPAnet and the internet. The craziness of the memex as an idea was purely relative to the time he was in. Looking backward from 2022, it looks like he was early, not crazy. The prescience of Bush's concept reminds us that we should make space for the futurists and (to some) crackpots to explore their wild ideas.

The memex was just one of Vannevar Bush's many contributions to the development of computers and the invention of the internet. The importance of his broader work coordinating scientific research led to the DoE research labs, the National Science Foundation, and more.

In part 2 I'll go deeper on ARPA, ARPANET, and how it came together.

You get pangs of jealousy with stories like this. The speed and conviction with which we used to take action!