Jobs Theory — Thinking in Demand and Supply

Res Extensa #8 :: Jobs to Be Done, supply-demand in the problem space, and thinking bottom-up

Hey everyone! I mentioned last issue that we bought a house, so my free time has been absorbed with home improvement activities for the past few weeks. The place is just about move-in ready now. (Pro tip: if you're considering removing layers of old wallpaper, I suggest learning to enjoy it rather than getting rid of it...) We're excited about the change of scenery and proximity to the family. Should be a fun summer this year. On to the issue...

You may have noticed some common themes at Res Extensa: complexity, emergent order, bottom-up processes, evolutionary systems. These concepts are pervasive, fascinating, and applicable in more categories than we often realize. If complexity and randomness are at the heart of so many phenomena, how can we embrace these effects rather than fighting against them? The best results come from harnessing the strengths of complex, distributed systems, while accepting the risks they bring that we have no control over anyway. It's about relying on emergence to produce something novel.

I've always liked this quote from Hayek (speaking here about economics, but conceptually could be applied to many fields):

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.

He's getting at a deep insight here: knowledge is too distributed, too emergent, and too unpredictable to divine from the center. "How do we know?" is a question that could be asked of any designer, planner, or government official, typically with answers that rely on models, abstractions, and assumptions about the world that could be dangerously wrong (see RE 4 where we went deep on this subject). Look no further than Leonard Reed's classic I, Pencil essay for example: even the knowledge to make something as trivial as a pencil doesn't live within a single person's head — it's scattered across hundreds of knowledgable producers working together to build something none of them can do alone. The market of distributed knowledge is like a peer-to-peer, super-parallel processing computer, able to compute results that no single computer can accomplish.

In the world of product development, this issue of distributed, arms-length knowledge is a barrier to designing solutions. Hell, it's a barrier to identifying what the problems even are, before we ever start producing an answer. If customers are nodes on a massive distributed network, we need to get down to the node level to dissect customer problems and work upward.

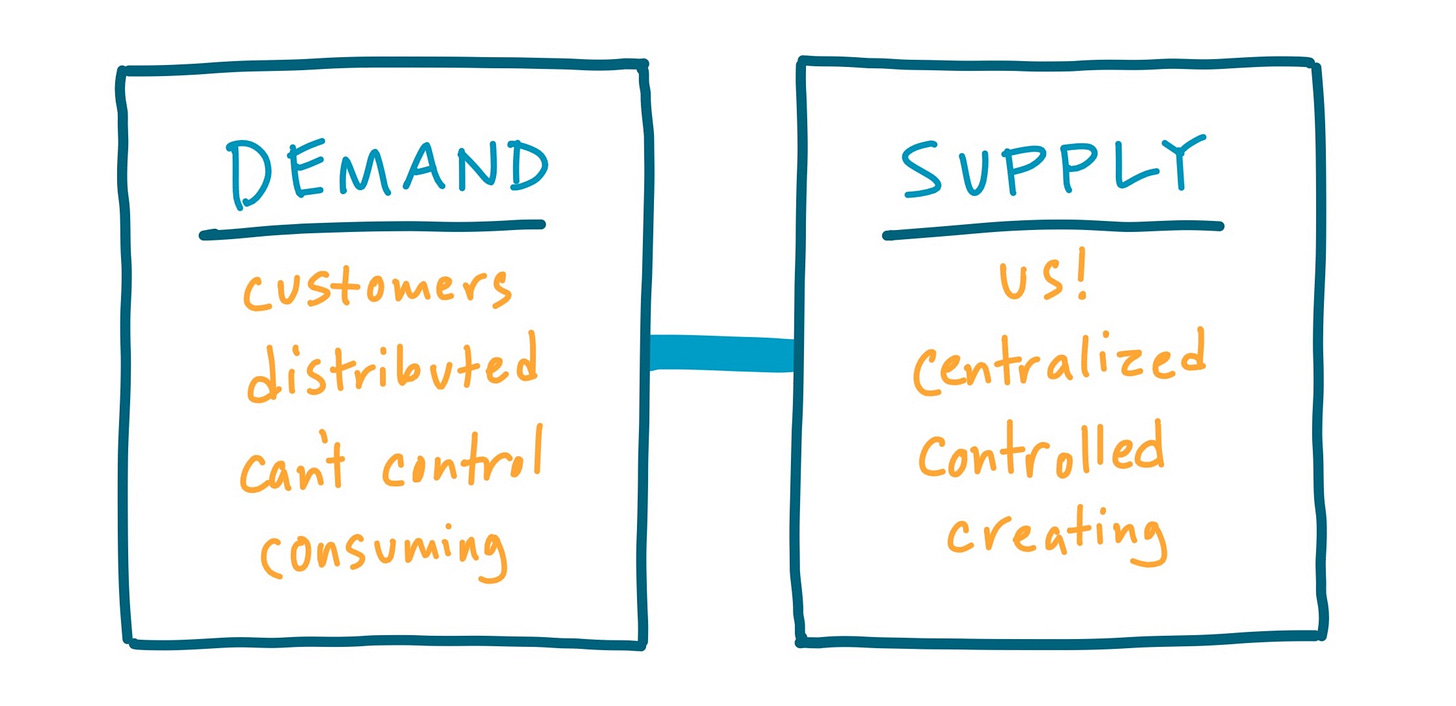

I've spent time recently thinking about the notion of "demand-side" thinking. When considering what to create to address a customer problem, product-builders tend to lean too far to the "supply" side of this equation, not spending enough time to understand the pushes and pulls on a customer, who lives on the demand side. Diagramming this out makes clearer what's going on from each side of this relationship:

If you create products, there's a natural comfort level with orienting yourself on the supply side: it concerns things we can control! But to create the most impactful solutions, we need to spend time first on the demand side, otherwise the information we're working with to guide our decisions over on the supply side isn't concrete — it's passed through abstraction layers before we have a chance to get our minds around it.

In this conversation from Demand Thinking, Ryan Singer and Chris Spiek discuss this issue. They use an example to demonstrate the problem: a user asking for permission controls in a software product. Once we hear that feature request, we're sitting over on the supply side thinking about what we know how to build — a settings panel, granular controls by user, access roles. "5 people asked for a permissions control, we need to add it." Lost is the fact that there was an underlying cause we're abstracted from. What was happening in the customers life that made them feel a need for controls? Was there a specific event that triggered a struggle or pain?

This demand-supply dichotomy appears (though not in those terms) in the Jobs to Be Done framework, a tool to help understand customer behavior. On the surface JTBD is for companies building products for customers, but its principles can be applied to almost any field in which there's a creator-consumer relationship (government-citizen, manager-employee, and similar dualistic structures).

An Overview of Jobs Theory

In its most basic form, Jobs Theory refers to customers "hiring" products to make progress against struggles in their lives. Clayton Christensen (of The Innovator's Dilemma and Disruption Theory fame) formalized the idea a few years ago, but similar roots and principles are found in other systems, too (like the Pain Funnel from the Sandler Sales program, to name one). The objective of Jobs Theory is to get at the underlying causes of customer behavior and decision making, even the social and emotional dimensions that influence decisions beyond tangible features and benefits of a product.

A typical approach from the supply perspective gets us thinking in terms of "what" and "how": what should we build and how do we build it? Jobs Theory puts us on the demand side and asks things of the customer like "when did you find you needed that?" or "why do you do this that way?" What we're looking for are the forces underlying the path of behavior.

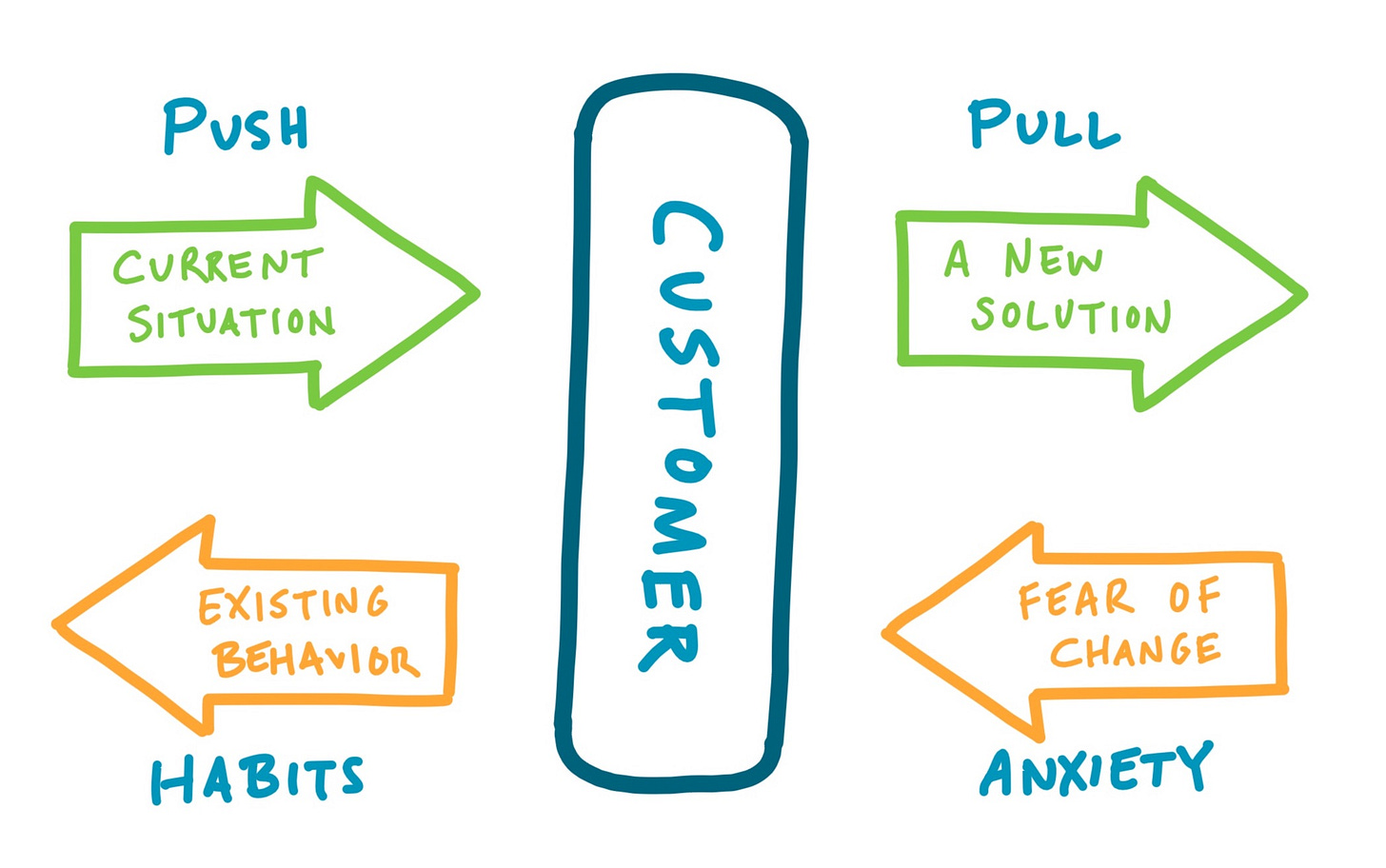

Getting outside of the supply box onto the customer's demand side sheds light on forces of progress and resistance, pushing them from the status quo and ones pulling them to future improvements:

You might think that companies have reams of customer data that answer these kinds of questions, and you’d be partially right. It's in vogue to be "data-driven" after all. But most data is collected and aggregated in a way that drives decisions from correlation, not causation. Marketing teams do this all the time (and it's a fine thing to do, to a point): defining a "persona" that tells us what an average user looks like. The problem is that averaging out all of the users doesn't give us a clear picture of the underlying motivating forces of any of the individuals. We're swamped with data, but confusing correlation for causation.

Viewing the world in terms of personas can be helpful for broadly communicating where you fit — for, say, internal discussion and team alignment — but can lead to dangerous correlative thinking; "this person that looks like this bought the product, this other person looks like that person, therefore they must also need my product". Not so fast! If the underlying chain of causation doesn't look similar, you may be way off in your prediction.

I've read two solid primers on the theory: Christensen's Competing Against Luck and Bob Moesta's Demand-Side Sales 101. Both of these use the lens of the company-customer model, but as you'll notice with a close read, these principles are insightful to apply in dozens of domains, not just the making and selling of products.

Jobs and Bottom-up Thinking

Jobs Theory gets us thinking from customer up, rather than solution down. Getting on the ground adds a layer of empathy you don't have when working through abstractions. A list of feature requests is piped through sometimes several translation layers which can shear off important context, like a game of telephone. We want that ground-up context, that experiential timeline to peel apart the interrelationships between factors in a customer's life to look for the nuances.

Designing purely from the supply side is a top-down approach. Without the ground-level context we miss out on non-observable-but-critical pieces influencing the problem. If we stay supply-side and want to gather data to describe problems, we end up applying so much noise reduction to the raw, observed customer experiences that we lose some of the important signal. Contrast these lists of sources used to assemble customer behavior data:

Supply-side: Existing expertise, comparisons to other customers, assumptions, expert opinion, industry analysis, sketches at the whiteboard

Demand-side: Playing ignorant and listening, watching users while they work, customer interviews, customer direct experience, observations from the field

Demand thinking acknowledges a world too diverse and complex for us to get our heads completely around. Reading an industry magazine, an analyst's report, or a focus group study doesn't get deep enough to help you find those specific "struggling moments", as Moesta refer's to them. It's still impossible to answer those "when" questions we want to understand.

This still leaves us with a challenge. As product makers, we can't make custom-tailored solutions for every permutation of customer struggle. Let's say we conduct 100 customer interviews to map out each's unique timeline. What do we do with that flood of detail? We can still evolve our thinking from the bottom-up. Look for similarities in the earliest phases of the JTBD timeline; do people start with a common set of first thoughts? Are there themes to what's happening with each as they're in "passive looking"? The first step to building a solution to a problem is to correctly identify the solution space you're even working in!

A reliance on analysts or consultants — third-party experts that define what the "market" wants using their own methods (sometimes solid, often questionable) — risks obscuring the detail needed to determine if we're in the right or wrong problem space. When problems are too generalized or nonspecific, there's a compulsion to spend time with what we know: our own product or service.

Experiential vs. Epistemic Knowledge

In Seeing Like a State, author James Scott describes the concepts of mētis and techne, two types of knowledge arrived at through different means — "practical" and "technical" knowledge, respectively. As Scott defines them, mētis thrives in complex environments, where specifics are difficult to measure or articulate exactly. Things like learning to ride a bike or how to bake bread are good examples; the quickest way to learn is through practice, trial and error. Techne on the other hand covers things that can be described in explicit, organized, detailed steps, consistent from case to case. Solving algebraic equations or assembling a piece of modular furniture, where the problem is codifiable into a universal, step-by-step instruction set.

This might be a strained idea, but bear with me (it's at most half-baked, maybe even quarter-baked). There are some interesting parallels here with some other bottom-up v. top-down dichotomies, not limited to the product-customer space:

There is no correct side, by the way. It may sound like I'm calling into question anything in the right-hand column. Rather, I'd say each of those has its place, as long as it's left-hand counterpart is respected and understood. A first-principles approach would have us begin with raw truths on the left-hand side, and work our way into theory development and constructs to describe things in more broadly applicable models and formulas.

Shaping Supply

This leaves us to figure out what to do on the supply side. Once the solution space is identified and there's a concrete problem definition, the next step is to begin formulating a response. In software we have "agile" development: adaptive, self-organized teams that use an iterative process to build products. But that only helps with how to get it done; it's not that useful in determining what exactly should be built.

In his book Shape Up, Ryan Singer describes the process (aptly called "Shape Up") they use at Basecamp. We’ve had good experiences applying its principles at Fulcrum; it helps fill in gaps that go undescribed by lots of other processes for collaborative building. It connects threads from the demand to supply side, from Jobs to Be Done on one end to your agile workflow on the other.

I actually saw Bob Moesta on Twitter hit this same point, calling Shape Up a good supply-side counterpart to Jobs Theory:

I found the core principles of Shape Up to be the most valuable. Setting scope boundaries, defining "appetites" (we're comfortable spending 6 weeks to solve this problem — is it still worth it if it takes more?), drawing diagrams that map elements to user behaviors (breadboarding), and predicting risks.

Once you start diving into the tenets of Jobs Theory, you start to think that way with everything. Since I read Christensen's take a few months back, every time I've found myself buying something (which has happened a lot with all the home improvement projects going on!), I'm thinking about the thought process of myself as a buyer.

As always, thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this, forward it onto your friends and colleagues or subscribe yourself if you haven’t. Let me know what you think of the newsletter so far! Also, check out my blog for more of my writing, or follow me on Twitter.