Form, context, and fit

Unfolding the forces of design problems with Christopher Alexander's model

What makes a design "work"?

Certain design approaches, whether in architecture, software, or tool-making seem to work so well, they evolve the whole design practice around them. They change the way design works in a particular domain from that point forward.

Some designs hit on such tight solution-problem fit — or form-context fit — that they become defaults.

Some adept craftsman came up with the claw hammer centuries back, and it still drives and pulls nails as well as ever. The simple paper clip has been holding sheets together for 150 years.

In biology, evolution spirals upward toward adaptations that work so well that they perpetuate for millions of years. The most tightly fit adaptations strike a near-perfect balance between specialized and generalized: they stick around even as the underlying environmental conditions change over time. Turtles developed their protective shells 200 million years ago. Squids evolved chromatophores for camouflage over 100 million years ago. An adaptation with good fitness sticks around.

When we consider effective design strategies for solving problems, the form-context fit model helps us frame and shape our understanding of the forces at work, and how we might design a solution to harness, dampen, or manipulate those forces.

In his 1964 book Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Christopher Alexander spends the first few sections describing this system of relationships, what he calls the "ensemble" of form, context, and the fitness between them.

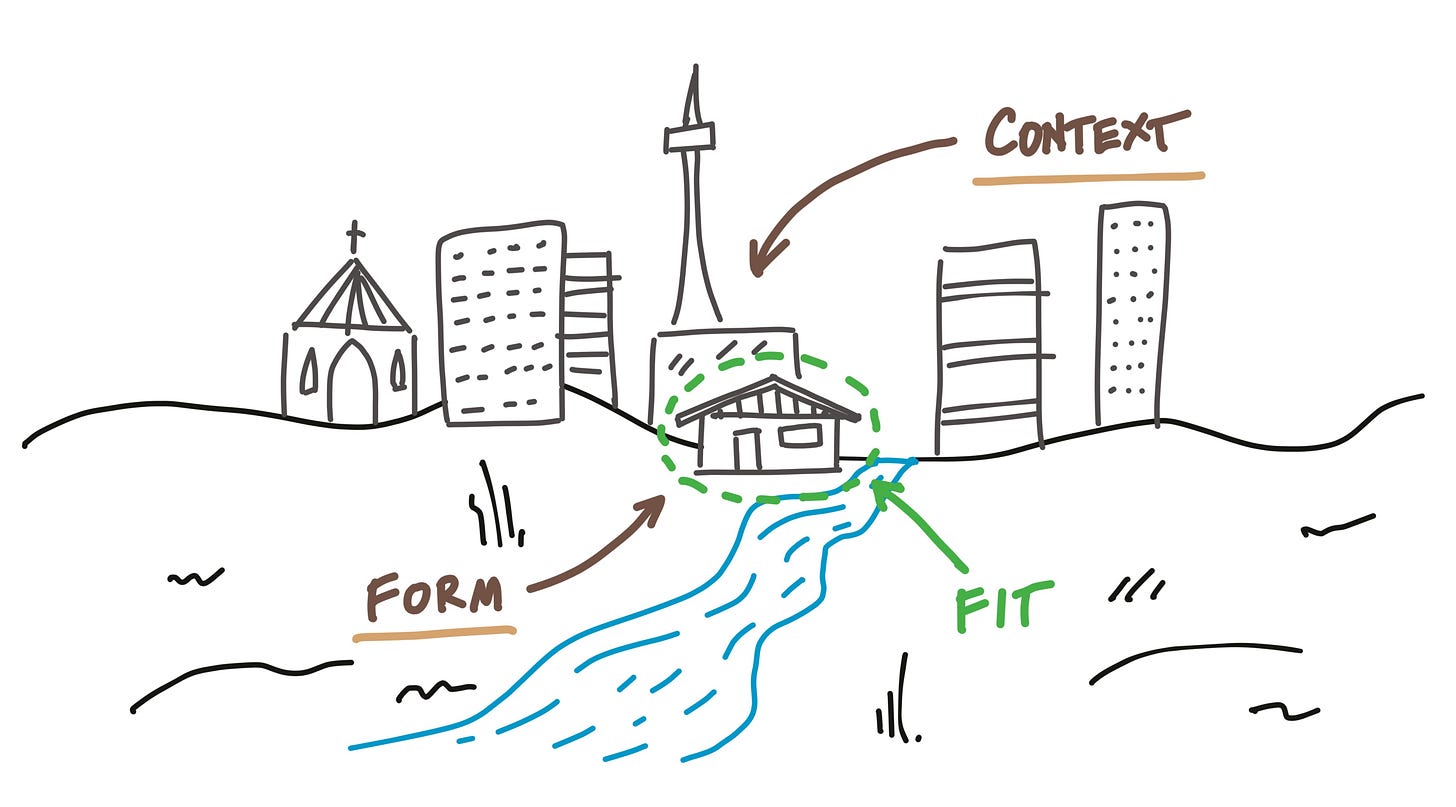

In Alexander's conception, the three elements work together:

Form is the shape, structure, and appearance of a thing – its physical or conceptual design. In architecture it's the floor plan, features, and physical look-and-feel.

Context refers to the environment or circumstances where an activity takes place, the setting that our designed form will work within. Context isn't limited to physical attributes — it also includes culture, social factors, time, user behavior, and more. The context presents a network of forces in an existing system: pushes, pulls, and dynamics for designers to contend with.

Fit describes how well the designed system matches its intended function or environment. It's a measure of suitability of the form to the context. A well-fit form aligns with the demands, constraints, and opportunities presented by the context.

Says Alexander:

The context is that part of the world which puts demands on this form. Anything in the world that makes demands of the form is context.

Fitness is a relation of mutual acceptability between these two. In a problem of design, we want to satisfy the mutual demands which the two make on one another. We want to put the context and the form into effortless contact or frictionless coexistence.

Design is the act of manipulating this ensemble. The search for fitness is the search for harmony in a complex web of forces. If we think of a context as an existing set of relationships, we seek to design a form that, once slotted into the existing network of forces, it improves in some material way the function, beauty, or enjoyment of life within the system.

Every design problem begins with an effort to achieve fitness between two entities: the form in question and its context. The form is the solution to the problem, while the context defines the problem.

When we speak of design, the real object of discussion is not the form alone, but the ensemble comprising the form and its context.

Design constraints in practice

In real-world design, we must consider more that just how a form fits physically or culturally into the context. Just because we can think up a tool to solve a problem, and that tool nestles nicely in with our user's existing box of tools, doesn't mean we're onto something yet. There are other factors involved in putting our solution into the world. To name a few:

Can we make the product for a cost a customer is willing to pay?

Can we deliver a solution faster than they find an alternative?

Can we continue to make our solution work over time?

Is it sustainable? And do they expect it to be sustainable?

A proper consideration of the context and effective form is a complex exercise of observation and experimentation.

We can't directly change the context; only the form is within the designer's control. It's as if the designer must decode a unique collection of interacting forces (like tumblers in a lock) and then design the key that aligns them perfectly.

Achieving fitness requires working from context outward. This aligns with ideas like jobs-to-be-done: we begin from the problem side (demand) and seek to generate a solution (supply) that addresses a pain (fit).

In the real world, the context is obscured. An essential element of design is the uncovering of the context's forces. The designer must unwind both sides: to study the context from all angles, to articulate the forces at work to the best of their ability, and to devise a form that works within this fluid environment. Alexander says of the designer's dilemma:

In the case of a real design problem, even our conviction that there is such a thing as "fit" to be achieved is curiously flimsy and insubstantial. We are searching for some kind of harmony between two intangibles: a form which we have not yet designed, and a context which we cannot properly describe.

Finding fitness by reducing error

Once we create a version of our form, we look for misalignments, places where our solution doesn't work in practice. Alexander points to a fascinating aspect of design evaluation: it's easier to identify poor fit than good fit. We naturally detect when something feels off or doesn't work as expected.

When a design element causes friction, when users struggle with an interface, when a chair becomes uncomfortable after sitting for an hour, these misfits stand out clearly. Good fit, by contrast, often goes unnoticed precisely because it flows so seamlessly with its context. When something fits well, it feels natural, intuitive, and "just right."

This asymmetry in perception is actually useful in the design process. As Alexander puts it:

The process of achieving good fit between two entities is a negative process of neutralizing incongruities, irritants, or forces that cause misfit.

This suggests an iterative approach to design: we create a form, test it in context, identify misfits, and adjust accordingly. Like evolution's process of natural selection, design improvement often works through the elimination of what doesn't work rather than direct leaps to perfection.

The salience of poor fit also explains why testing and real-world deployment are so crucial. Designers might be blind to the misfits in their own creations, while fresh eyes immediately notice what doesn't work. The ultimate judge of fit is always the context itself: how the form performs in the actual environment for which it was designed.

Form-context fit is a useful lens for design, in any discipline. Viewing design as the crafting of forms that harmonize with their contexts, gives insight into why some solutions endure while others fail. The most elegant designs aren't necessarily the most complex or flashy, but those that achieve an invisible balance with their surroundings, responding to constraints while opening new possibilities. The designer's task is to uncover the hidden forces in the context, craft a form that addresses these forces effectively, and continually refine to eliminate misfits. When we achieve this delicate balance, we create designs that don't just solve problems today, but can evolve along with changing contexts over time, like the paper clip and claw hammer that have stood the test of centuries.