Composable Notes, Supply Chains, & Reading Updates

Res Extensa #13 :: Using atomic notes for composable ideas, supply chains as complex nested systems of complex systems, and some reading updates

Welcome back. The cool weather is on its way here in Florida (i.e. it’s not 85°+ every day) and the holidays are upon us. A great time of year to be in this part of the world.

Recently I've been reading a lot more about systems: complex and interconnected networks of stocks and flows, how we can or should create them, and what to do when they fail us. Gall's Law has figured heavily into my thinking lately:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.

Composing complex systems from stacks of simpler systems is how we should think. In knowledge-work, there's a tendency to equate complexity with power or advancedness. Don't get too clever too early.

Concept-based Notes and Composable Ideas

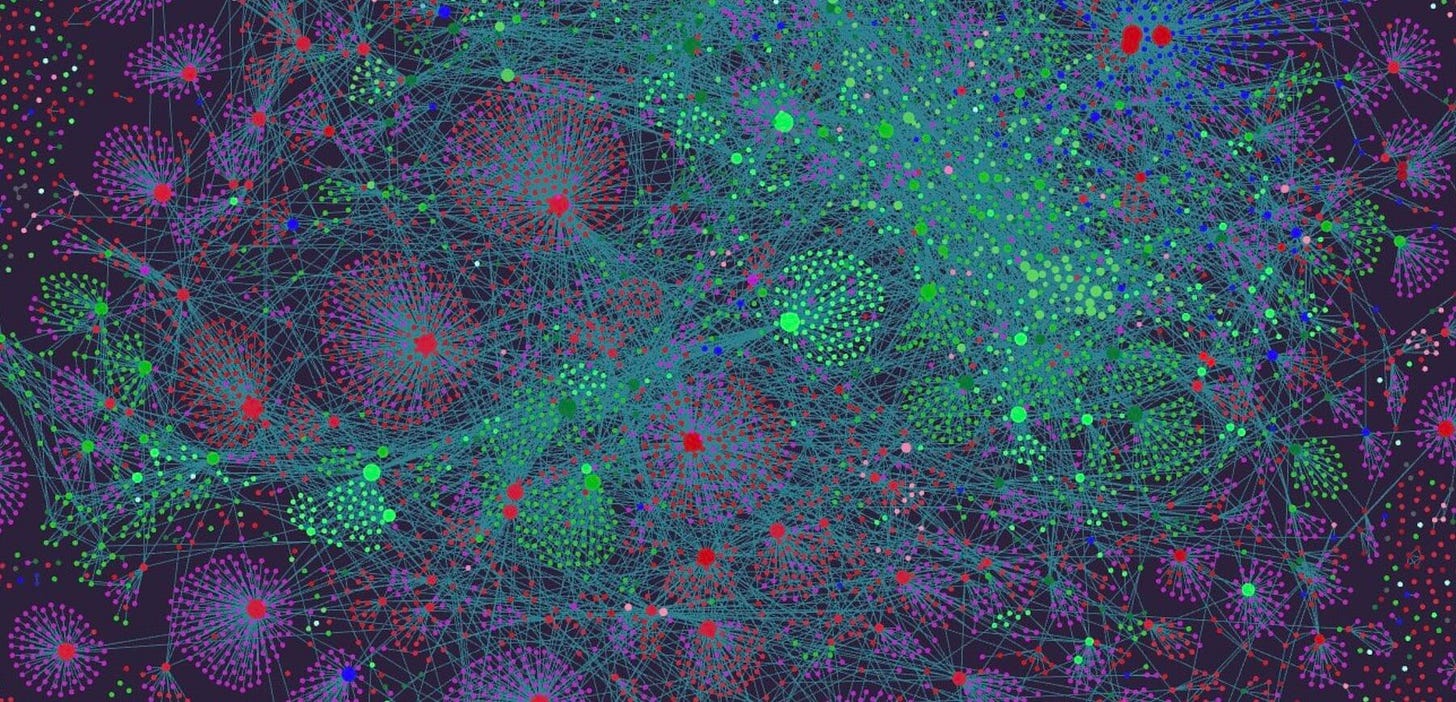

In a note-taking system, if a note represents a single concrete idea, we want to make the idea as atomic as possible, so we can find and stitch them together into an interconnected web of ideas. We want composable building blocks.

Composability helps us stack, mix, and repurpose ideas. To correlate them and find the relationships between them. Prose is an excellent medium for consumption, for diving deep on a particular topic. But with a prose format for documenting ideas (through notes), it's harder to relate shared ideas across domains. Prose makes ideas easy to expand on and consume, but difficult to decompose into reusable parts. Decompose too far, though, say into individual words and letters, and the information is meaningless. We want a middle ground that can effectively convey ideas, but is also atomic enough to be decomposed and reused. We want idea Legos.

In Self-Organizing Ideas, Gordon Brander contrasts the linear, difficult to break down expansiveness of prose with something more like an index card. With index card-level division, ideas can now be expounded on at the atomic level, but also cross-referenced and remixed more easily than long-form prose. With the Zettelkasten, Luhmann devised a system of just that: numbered index cards that could reference one another. If you use a system like this for note taking, it's a fun exercise to actually take a batch of 3-5 permanent notes at random and look for relationships. When I've done this, pulling out 2 arbitrary permanent notes, it often sparks new thoughts on them, and in the best cases, entirely new atomic notes.

Within our knowledge systems, we should strive for that right altitude of scope for a particular note or idea. Andy Matuschak says "evergreen notes should be atomic." In my system, I make atomic notes that are concept-based, with a declarative format that prompts me to keep the note focused around a specific idea. Just scrolling through the list now, I see ones like:

"Traditions are storehouses of trial and error"

"Novelty in startups is higher than predicted"

"Knowledge is the biggest constraint in product management"

With a format like this, each note is structured as a claim or idea, so it's densely linkable inline within other notes. So when reading a note, the cross-link to another idea can appear seamlessly within the text. Using a concept-based approach, we might find serendipitous connections we weren't looking for. Andy says:

If we read two books about exactly the same topic, we might easily link our notes about those two together. But novel connections tend to appear where they’re not quite so expected. When arranging notes by concept, you may make surprising links between ideas that came up in very different books. You might never have noticed that those books were related before—and indeed, they might not have been, except for this one point.

Novel ideas spring from concocting new recipes from existing ideas. Composable, atomic ideas make it more manageable to toss several disparate ones together to experiment with new combinations.

Gordon has been writing lately about his work on Subconscious, and the possibility of software-assisted self organization of ideas. This is a super intriguing concept, and exactly the sort of reason I'm interest in computers and software — for their ability to help us think more creatively, do more building, and less rote information-shuffling.

Systems and Supply Chains

You can't touch current events online (at least in circles I follow) without running into 25 opinions on what's causing our supply chain lock-ups.

Global supply chains are just about the most interesting examples of systems by the traditional systems thinking definition. They have stocks and flows, feedback loops, and nonlinear response dynamics, plus they're highly visible, global, and impact each of us in very direct ways. Because everyone on earth is impacted directly by these problems, we're hyper-aware of the issues, which drives the experts out of the woodwork to flex their Dunning-Kruger muscles.

My diagnosis in all the reading I've done is, generally, if you think there's a single pinch point or monocausal explanation, you don't understand how systems work.

That being said, I always love to hear what Venkatesh Rao has to say on complex systems like this. As much as we think of supply chains as an "old world" system of technologies, Rao points out that the analysis on the issue so far "seems to adopt the posture that we are talking about a crisis of mismanagement in a well-understood old technology rather than a crisis of understanding in a poorly understood young one." Meaning, an enormous number of the contributing innovations to the modern supply chain are a decade or two old. Automation, algorithmic cargo sorting, the buy/sell economics of e-commerce, epic Panamax super containerships. All of the novel contributing innovations aren't as well understood as we think they are, especially the impacts they have when they fail. It's worth remembering that due to its sheer size and entangled complexity, a global shipping supply chain is a networked combination of entities designed individually, but interfacing with one another. No committee sat down and laid out the infrastructure, policy, transportation protocols, or decision making processes that would get silicon from a factory floor in Shenzhen to the chip in the car in your driveway. Rao reminds us to think of this network as an emergent one:

The thing is, a supply chain is mostly an emergent entity rather than a designed one, and its most salient features often have very little to do with its nominal function of getting stuff from Point A to Point B. That’s just the supply chain’s job, not what it is. What it is is a homeostatic equilibrium created by billions of sourcing decisions made over time, by millions of individuals at businesses around the world making buying and selling decisions over time.

When a complex system is breaking down, when there are stopped flows or undesirable negative feedback loops, we have to carefully pick apart the system's interrelationships to find root causes. In an interesting could-only-happen-on-Twitter turn of events a couple of weeks ago, Flexport founder Ryan Petersen possibly single-handedly unplugged one of the many possible clogs in the system when he cataloged Long Beach Port issues in a thread, chasing down one example bottleneck in the local area's container stacking limitations:

I suggest clicking through and reading the whole thread. The gist was: there aren't enough trucks to pick up and haul the unloaded containers, so they need to be put somewhere on-shore. The stockyards used for holding containers are subject to regulations where they can't stack them more than 2 units high. Therefore, an ever-growing fleet of ships sit at anchor until the clog is removed. But even this simple political solution isn't the only friction — what's causing the lack of trucks and/or drivers? Why don't we have fallback locations ships can be rerouted to? We have a complex and fragile system subject to too many failure points. Big monocausal opinions don't paint a realistic picture, even if there's truth in them. "It's all the longshoremen unions!" or "it's consumerism!" or "we should reshore all manufacturing from China!" are all claims with some possible merit to them. But responding to only one of those will do next to nothing. The system will evolve around changes you make.

Supply chains are emergent functions of millions of individual interactions between nodes on a network. Changing individual policies doesn't cure all of the system's ills, but neither does sitting around blaming one another with simplistic claims about who or what the problem is.

Reading Updates

For those unfamiliar, I keep an up-to-date library of my reading activity on my website. I've been gradually adding my notes from books I've read (you'll see the little paper/pencil icon for ones with summaries and notes). Last month was a month of fiction, finishing a re-read of Dune in prep for the movie, a re-read of the start of Gaiman's Sandman series, and an excellent, super unique excellent science fiction piece called There is No Antimemetics Division by independent writer Sam Hughes.

The story exists within a shared collaborative universe developed and contributed to by hundreds called the SCP Foundation. The community contributes to a shared wiki where anyone can write new stories or develop new paths to explore within the world. The Foundation is a quasi-governmental secretive organization responsible for "securing, containing, and protecting" against supernatural, paranormal phenomena called "SCPs". Some of them are extremely weird and excellent fodder for sci-fi creativity. Very X-Files-esque. It's interesting to see a collaborative pseudonymous, community-driven worldbuilding like this. I'm sure other media will continue to spin off of it.

TINAD expands on a handful of the individual stories you'll find on the wiki. Hughes is a phenomenal writer — engaging, wildly creative, experimental. I also read another of his called Ra last year, a story where magic is real, a branch of quantum physics.

I also just published some thoughts on Seeing Like a State, which I've got loads of notes from that I still need to format up for publishing. In case you didn't see it, RE 4 went deep on James C. Scott's idea of legibility and it's relevance across different themes.