Between the plan and reality

Improvisation, experience, and adapting in motion

One of my favorite YouTube channels is the Perkins Builder Brothers. This group of custom home builders in Western North Carolina takes their viewers along for the ride during the complete construction of homes: from site layout to foundations to framing to decks. All the finishings and details, broken down in day by day video journals showcasing the process. They fill their videos with tips and explainers in how houses come together, and as viewers we get to see the fun, the mess, and all the minutiae a builder has to deal with to stand up something as basic as a two-bed, two-bath mountain cabin.

The longer you watch, the clearer it becomes that some of the most important work happens in the gaps between the plan and reality. In every single video you’ll see them wrestle with how to handle the unplanned. And I find it fascinating to watch experts figure things out on-the-fly.

What separates experienced craftsmanship from on-paper technical expertise isn’t just what you know ahead of time. It’s how you respond when you find out the plan is insufficient.

When preparation gives way to judgment in the moment, we’re forced to improvise.

I’m not referring to improvisation as an intentional choice, like the work of a comedy troupe or a jazz trio. I mean the kind of improv we’re all forced into when we encounter the unexpected. When reality diverges from the plan, you adapt. How well you do that is a function of experience, pattern recognition, and having trained the right muscles.

In home construction, as in all kinds of lines of work — business, product development, engineering, writing — no matter how meticulously you plan ahead, improv is how you course correct, how you fill in those unshaded areas you hadn’t planned to encounter.

To some it might come as a surprise, but much of the time in construction, the plans drawn up by an architect leave out many of the details required to get the thing built. And not just trims and ornamentations; typical drawings are often missing structurally important details. Or they’ll define a configuration of parts that’s physically impossible.

This isn’t because architects and engineers don’t know how to build. Often details are explicitly missing with notes to “leave final implementation to the builder.” No matter how specific the blueprints, some things are left unanswered.

Reality has a surprising amount of detail.

It’s interesting to observe how experts adapt in motion. There’s this incredible mixture of technical knowledge and tacit experience involved in adapting well. No amount of book study gives the home builder enough of the hands-on knowledge needed to work with natural materials like wood warping, twisting, and expanding, or to mix their concrete a little dryer than the instructions say when it’s humid or rainy. Or if you invert this, having no technical understanding of the building code book or how to read a floor plan won’t have good results either. You have to have both. This combination of skillsets arms the craftsman with more tools with which to adapt.

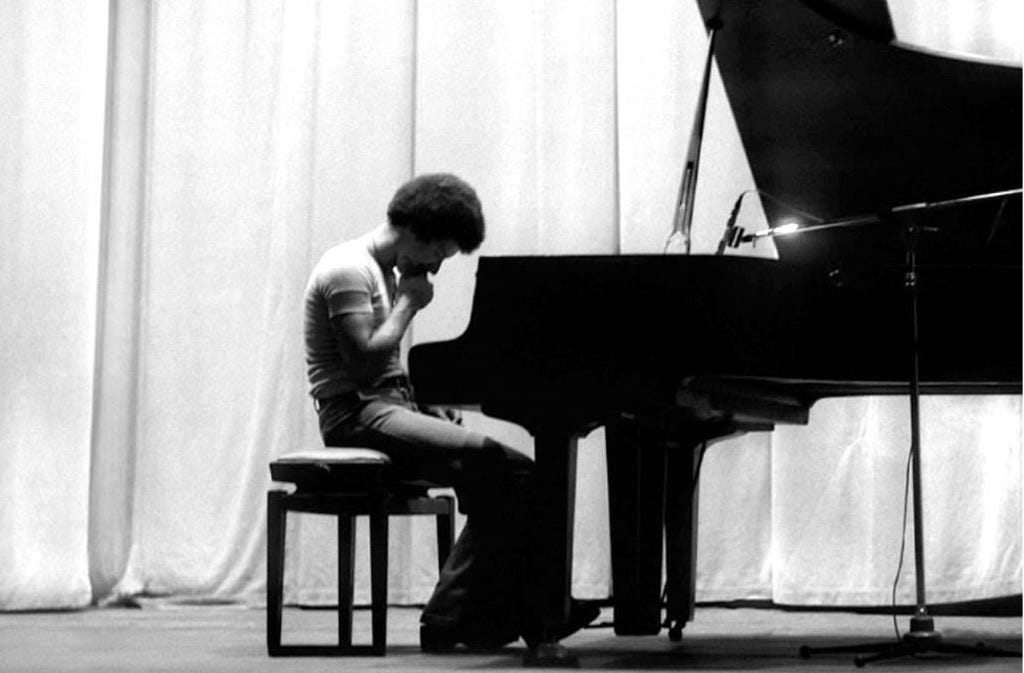

“Life is a lot like jazz… it’s best when you improvise”

–George Gershwin

Improvisation isn’t simply “making things up.” In the world of jazz, the soloing pianist isn’t just winging it and hammering keys indiscriminately. They’re working within a key, using scales and known phrases, and playing within a constrained playground of options. Their prior knowledge of harmony, chord voicings, and technique gives them a foundation to build on and a set of quickly-retrievable building blocks to work with. The richer this foundation, the more prepared they are to “make it up as they go.”

When the Perkins crew runs into an unplanned situation on the job site with no prescribed solution, they’re left to their knowledge of similar past situations, the local building codes, and their understanding of tools and materials to figure out a way forward. They’ve got to adapt.

Not only that, they don’t have hours or days to sit around and think up the best solution. It’s a game of trade-offs. Often the best solution to the problem at hand is the one they can devise in the next hour, rather than the perfect one on paper. If an electrician or drywall installer is waiting on a detail with window framing to get handled before they can start, that hurdle halts the entire project.

Between the constraints on time and the challenges of working on remote sites (you only have what tools and materials you’ve got in the truck right now), the array of options is limited.

Improvisation is a skill you can intentionally nurture, in any field. It’s why practice is so critical to skill development. Reading the books and studying the theory is certainly part of the foundation. But there’s no substitute for the tacit practice, for the applied exposure that reality forces on you. Planning is part of the battle, but adaptability comes through trial and error.

Just because you have a plan doesn’t mean you won’t have to adapt. The best builders, musicians, and product makers aren’t the ones with the most detailed plans. They’re the ones who’ve practiced enough to adapt without panic when the plan dissolves. Improvisation isn’t freedom from structure; it’s what structure looks like when it’s been fully absorbed.

Love the jazz analogy here. The Keith Jarrett example nails somethin most people miss about improv. Back when I was learning guitar, my teacher used to say real improvisation is like having an internalzed library of licks, not random noodling. What seperates good builders from mediocre ones is that absorbed vocabulary, not just memorized plans.

I realized a while ago that my expertise in content and communications can fundamentally be boiled down to "problem solving in a specific domain." The ability to acknowledge and work with constraints, rather than insisting on a perfect reality that doesn't exist, is one of the most important skills in actually getting things done.